This month, Dipti Mehta and Rupal Patel discuss everything you need to know about the classification and management of endodontic-periodontal lesions.

As specialists in endodontics and periodontics, we find the diagnosis and successful management of endodontic-periodontal lesions (EPL) one of the most challenging aspects of day to day practice life.

In this article we aim to review the classification of EPL and discuss diagnosis and management with a few clinical cases.

What are EPL?

EPL are clinical conditions involving both the pulp and periodontal tissues and may occur in acute or chronic forms (Herrera et al, 2018).

The most common signs and symptoms of EPL are:

- Deep periodontal pockets

- Negative or altered response to pulp vitality tests, being aware of the accuracy of these in multi-rooted teeth.

Other reported signs and symptoms include:

- Bone resorption in the apical or furcation region

- Spontaneous pain or pain on palpation and percussion

- Purulent exudate

- Tooth mobility

- Sinus tract – often located at the gingival margin

- Crown and gingival colour change.

Understanding EPL

When taking the patients’ history, it is important to gain an overall understanding of the caries and periodontal risk, parafunctional habits and any history of trauma. Examination will include a full periodontal assessment.

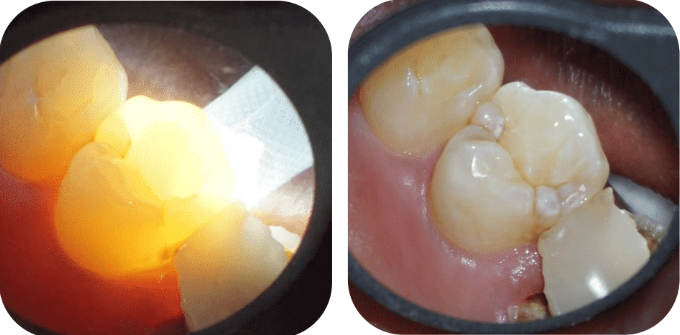

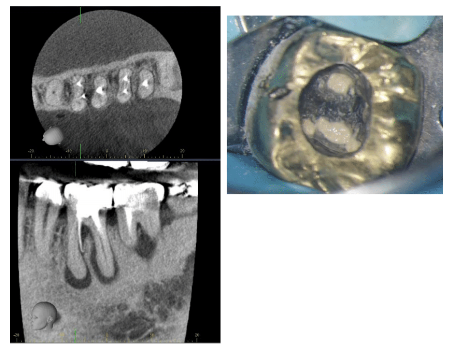

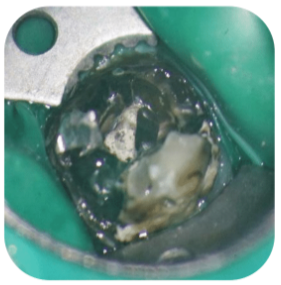

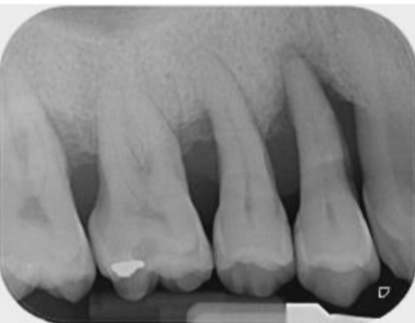

A deep narrow pocket around the tooth could be suggestive of a crack (Figure 1), root fracture or it may be the manifestation of a sinus tract. Additional special tests beyond vitality testing and periapical radiographs may need to be considered, including transillumination (Figures 2a and 2b) to identify a crack or a small volume CBCT scan.

Multiple pathways of communication for pathogens between the pulp and periodontal tissues exist. These can be broadly divided into anatomical pathways and those caused by structural failure of the tooth.

The apical foramen is generally thought of as the main anatomical route of communication. However, additional routes include lateral canals (including furcal canals), dentinal tubules and developmental anomalies. Structural failure pathways include fractures of the tooth/root and perforations.

Generally, when we consider perforations, these may be iatrogenic in nature or as a result of resorption or caries.

It is important to understand the effect of periodontal disease on the pulp. Although studies show that in most cases the effect is limited, we know periodontally involved teeth have a propensity for increased calcifications within the pulp, narrower canals and fibrotic pulp tissue, all of which can make endodontic management of these teeth more challenging.

An established EPL is always associated with varying degrees of microbial contamination of the dental pulp and the supporting periodontal tissues. The primary aetiology of these lesions might be associated with:

1. Endodontic and/or periodontal infections

These are primarily associated with a carious lesion that affects the pulp and secondarily affects the periodontium.

Alternatively, periodontal pathogens secondarily affect the root canal space. Literature tells us this is rarer (Langeland et al, 1974). Finally, these events can occur concomitantly.

2. Trauma and/or iatrogenic factors

This includes iatrogenic perforation of the tooth related to endodontic access cavity preparation, root canal instrumentation or post preparation.

Additionally, root fractures or cracks can contribute to the development of EPL, as can perforations from external root resorption.

Classification of EPL

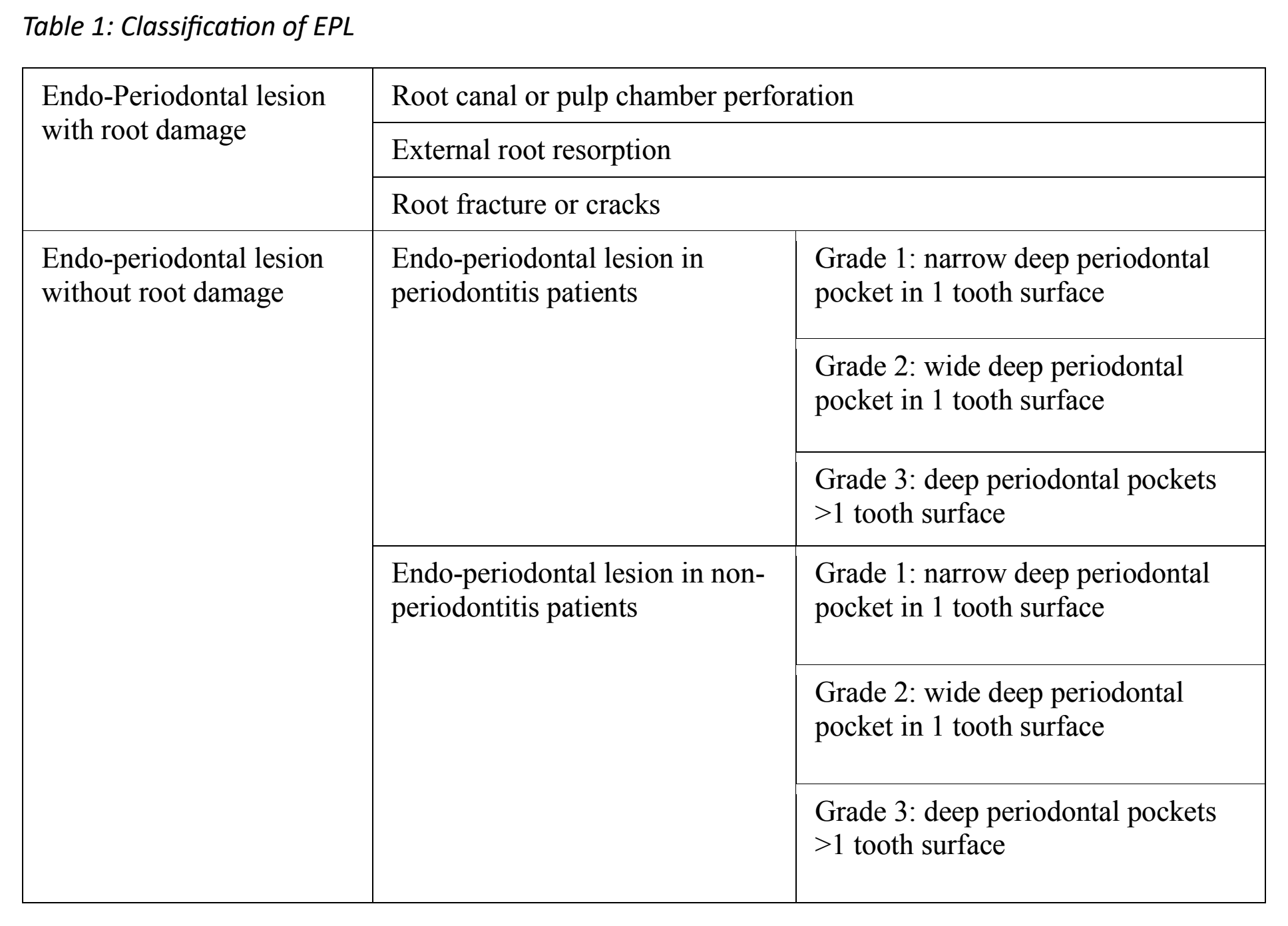

When the periodontal classification was updated in 2017, a new structure for classifying EPL was also created.

The change from the classic primary endodontic, primary periodontal and true combined lesions (Simon et al, 1972) was made because the source of the infection is not always considered relevant to treatment and information on the history of disease is not always available at the time of diagnosis.

The new classification is based on the present disease status and helps to determine the first step of treatment planning: treatment or extraction of the tooth.

1. EPL with root damage.

Although, Herera et al 2018 say prognosis is hopeless in these cases, from an endodontic standpoint, the prognosis can be variable.

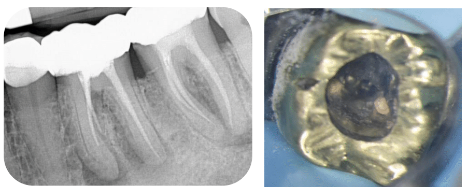

The main prognostic factors are the extent of both the root damage and microbial infection. For example, when assessing the prognosis of a perforated tooth, we consider when the perforation occurred, location, size and reparability (Figure 3).

With cracked teeth we assess the extent of the crack and presence of a narrow pocket. If the root damage cannot be repaired or contained, the extraction of these teeth may need to be considered (Figure 4).

2. EPL with no root damage in periodontitis patients

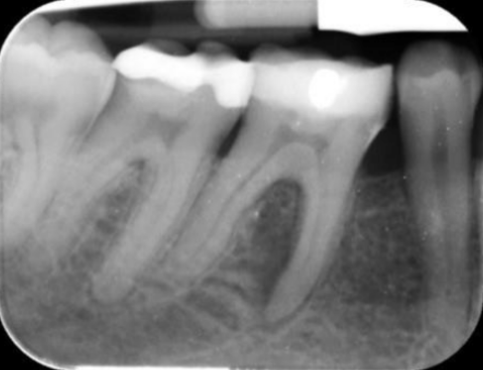

Significant periodontal destruction (generally to the apical foramen) is required to cause pulpal pathology. Consequently, the prognosis of these teeth is generally seen as guarded to hopeless and extraction may need to be considered (Figure 5).

If treatment is being planned, endodontic treatment should occur prior to periodontal management after allowing for a period of endodontic healing. Periodontal management may range from initial non-surgical to surgical treatments including regenerative surgery.

Root resections or hemi-sections are less frequently planned in view of the overall cost of treatment and the advancements in implant dentistry.

It is important to remember that, invariably, these patients are likely to have other areas of active periodontal disease which needs to be managed in the early phase too.

3. EPL with no root damage in non-periodontitis patients

This is attributed to pulp necrosis and drainage of the apical infection via the periodontal ligament space (usually through lateral, accessory and furcal canals). Control of the endodontic infection results in a favourable prognosis.

Developmental defects such as root grooves also fall into this category – these are less predictable to treat and often require a combined approach. The overall prognosis in this category will be related to the severity of the EPL, ie grading. The more severe the grading, the worse the prognosis.

As above, endodontic treatment should be completed first. After a period of endodontic healing, the periodontal status is reviewed (8-12 weeks). Often periodontal health will have been achieved, with a resolution of the pathological probing depths. If pocketing remains, periodontal treatment should be undertaken (Figure 6).

In summary

The management of EPL can be simplified by considering the present disease status and the treatment prognosis at the diagnosis phase.

When considering saving the tooth, endodontic treatment (if appropriate) is always carried out prior to periodontal management. An overall holistic approach to the patients’ care should be considered.

References

- Herrera D, Retamal‐Valdes B, Alonso B and Feres M, (2018) Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo‐periodontal lesions. Journal of clinical periodontology 45:S78-S94

- Langeland K, Rodrigues H and Dowden W (1974) Periodontal disease, bacteria, and pulpal histopathology. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology 37(2): 257-270

- Simon JH, Glick DH and Frank AL, (1972) The relationship of endodontic‐periodontic lesions. Journal of periodontology 43(4):202-208.

Catch up with the Endodontics 101 series:

Follow Dentistry.co.uk on Instagram to keep up with all the latest dental news and trends.