Although there’s no way of completely removing dental aerosols, Anna Middleton gives her three tips to reduce them so the risk is minimal.

Although there’s no way of completely removing dental aerosols, Anna Middleton gives her three tips to reduce them so the risk is minimal.

There is a long history of infections transmitted by an airborne route.

Even before the discovery of specific infectious agents, we recognised the potential of infection through an airborne route.

What is an aerosol?

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in air or another gas.

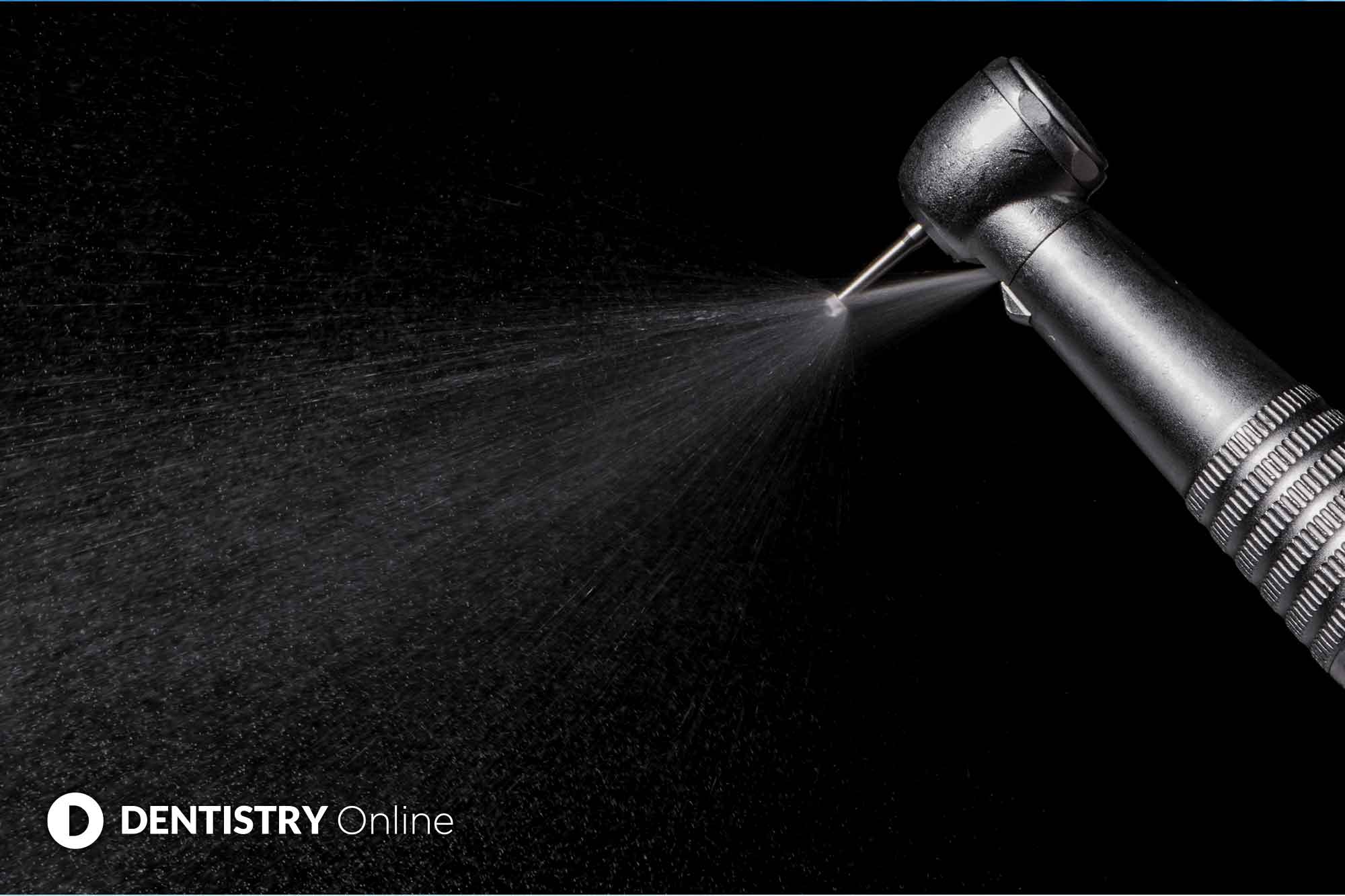

An aerosol cloud is often clearly visible during dental procedures. This cloud is evident during tooth preparation with rotary instruments or air abrasion, during the use of a three in one, ultrasonic scaling and during polishing or using ‘airflow’.

This cloud is a combination of materials originating from the treatment site and from the dental unit waterlines. As we know, it is common for the patient to comment on this cloud.

Why are they a problem?

Because we produce aerosols and droplets during many dental procedures, they are a transmission vehicle for infections.

The use of them in dentistry poses a great challenge due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Coronavirus is detected in the mouth, nose and throat. The main transmission path is through droplet infection.

Aerosols differ from droplets and spray mist. Due to their smaller particle size (<50μm) they can carry several meters away and be detected in the room air for up to 30 minutes.

How can we reduce them?

Aerosols and splatter generated during dental procedures will always have the potential to spread infection.

No single approach or device can minimise the risk of infection to clinicians and patients completely.

A single step will reduce the risk of infection by a certain percentage. Another step added to the first step will reduce the remaining risk, until such time as the risk is minimal.

We describe this as a layering of protective procedures. The following are my top three universal precautions.

1. Pre-rinse

It is well documented that the use of a pre-procedural mouth rinse with a chlorhexidine for 30-60 seconds reduces the bacterial load in aerosols by up to 70%.

Chlorhexidine is an effective antiseptic for free-floating oral bacteria. However, we know it does not affect bacteria in established plaque, does not penetrate subgingivally, will not affect blood coming directly from the operative site and is unlikely to affect viruses and bacteria harboured in the nasopharynx.

Mouth rinses containing hydrogen peroxide do have an effect on viruses. However, there is currently no data regarding its effectiveness on COVID-19.

Based on the data available covering its effectiveness on other viruses, it suggests this could be just as effective on COVID-19.

A recommendation is that patients gargle and rinse with hydrogen peroxide for 15-60 seconds at the beginning of each treatment. They should repeat this process after 30 minutes if needed. Then rinse with chlorhexidine for at least 60 seconds.

While pre-procedural rinses will reduce the extent of contamination within dental aerosols, they do not eliminate the infectious potential of aerosols.

2. Universal barrier/rubber dam

As we know, the use of a rubber dam will eliminate virtually all contamination arising from saliva or blood.

If we use a rubber dam, the only remaining source for airborne contamination is from the tooth that is undergoing treatment.

This will limit aerosols to airborne tooth material and any organisms contained within the tooth itself.

In certain restorative procedures, such as subgingival restorations and say the final steps of a crown preparation, it is often impossible to use a rubber dam. The use of a rubber dam is also not feasible for periodontal and hygiene procedures.

This is a concern. We always perform these procedures in the presence of blood and saliva. The instruments also produce a high level of aerosol.

Something to consider is the use of an Optragate – from Ivooclar Vivadent. It is a latex-free lip and cheek retractor. They are flexible and make it comfortable to wear and assist patients in keeping their mouth open.

Lips and cheeks are evenly retracted around the mouth. This lends itself to a more relaxed and efficient treatment procedure and increases visibility and access.

3. High-volume evacuator (HVE)

Regardless of where you are using a rubber dam, Optragate or nothing at all from a practical point of view, it is easiest to remove as much airborne contamination as possible before it escapes the immediate treatment site.

The use of a high-volume evacuator, or HVE, reduces the contamination arising from the operative site by up to 98%.

So, what qualifies a suction system to be classified as an HVE?

Firstly, size. The usual HVE in dentistry has a large opening, typically 8mm or larger.

Secondly, volume/flow speed. HVE need to remove a large volume of air (up to 100 cubic feet of air per minute) and 300 litres per minute of fluid. The small opening of a saliva ejector does not remove a large enough volume of air to be classified as an HVE. It removes 0% of aerosols, but works as a good combo to have in the patients mouth while you are using the HVE.

With this in mind, do make sure your suction unit is regularly serviced, in good working order, no blockages, no rips or tears in the tubes and that the suction doesn’t drop when someone else is using it.

These will reduce efficiency. Less than 300l per minute and you won’t hit that 98% of aerosol removal.

I personally like and use a Purevac. It has a wide bore, slim shank, angled and has a mirror, which is very good quality and does not fog up.

We can also autoclave it too. Which is great news for the environment and less plastic waste.