James Tang offers practical advice on activating your core to combat musculoskeletal dysfunction commonly associated with dentistry.

James Tang offers practical advice on activating your core to combat musculoskeletal dysfunction commonly associated with dentistry.

One of the most common causes of musculoskeletal lower back pain is core dysfunction, and this is usually caused by prolonged sitting on a stable surface; there is therefore no need for the muscles of the core to stabilise the spine. Over a period of time, these core muscles become atrophic and dysfunctional, and they are no longer able to support and protect the spine when needed.

So, what exactly is the core? I suspect that you think the core is the rectus abdominis, commonly known as the six-pack. Actually, when we talk about the core, it is not just one group of muscles, it is in fact the effective and coordinated contraction of all these three layers of muscles, from the deep, the middle to the outer layers, that determines the level of core function.

The definition of the core is the ability of your trunk to support your limbs during functional activities, allowing your muscles and joints to perform in their safest, strongest and most effective positions. It is important because any movement that uses the whole body requires a strong core to stabilise the spine and to transfer power between the upper and lower halves (through the pelvis).

Spinal movement

Movement of the spine can be divided into the following movements:

- Gross physiological movements – such as bending or twisting the torso. This is the job of the superficial layer of muscles of the spine

- Accessory movements – these occur alongside the gross physiological movements and take place within each vertebral segment. Deep muscles that control these intricate accessory motions include the interspinalis, rotators and intertransversarii. They are not very strong and if the core musculatures are not effective in stabilising the spine, these tiny muscles will be used excessively and they may go into spasm, thereby causing lower back pain.

The middle layer is the main component of our core musculatures and it consists of the following components:

- Diaphragm (at the top of the abdominal cavity) – a respiratory muscle that contracts downwards to increase the intra-abdominal pressure

- Pelvic floor – a group of muscles at the base of the pelvis, which hold the organs

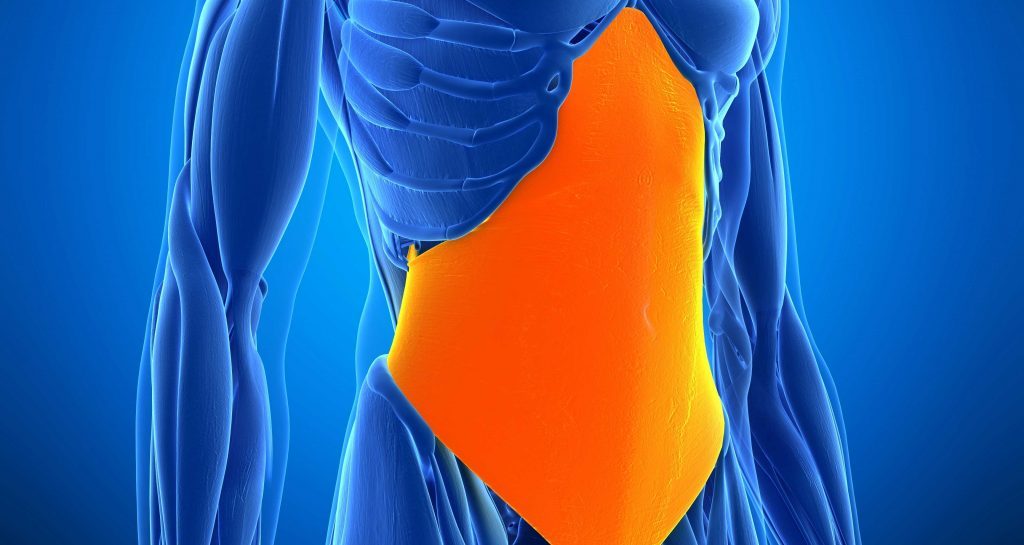

- Transversus abdominis (TvA) – this forms a belt around the torso and functions by drawing the waist in to increase the intra-abdominal pressure

- Multifidus – a series of smaller muscles that connect the transverse processes to the spinous processes. They help to provide rotation and extension of the spine.

During functional movements, these muscles should contract in an orderly manner to increase the intra-abdominal pressure, like an inflated balloon compressing against the spine and stabilising it. If these core muscles do not contract in the right order (deep to outer layers), or the deeper core muscles lack strength, this can lead to an over-reliance on the large, global muscles closer to the surface (eg, the erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, rectus abdominis, external obliques, glutes etc) to stabilise the trunk.

These superficial muscles are primarily responsible for the gross physiological movements of the spine and consist mainly of type IIa and IIb fibres. They are strong but quick to fatigue and are not designed for endurance or postural activities such as stabilising the spine.

Over-reliance on these groups of muscles causes them to overwork, leading to the formation of trigger points in these muscles – a common cause of lower back pain.

Activating your core

The most important component of your core is the TvA. It functions like a corset to stabilise the lower back and pelvis before movement of the limbs. Research suggests that TvA and multifidus activation is diminished in patients with lower back pain.

The TvA wraps around your torso. It originates from the iliac crest, inguinal ligament, thoracolumbar fascia and the lower six ribs, inserting to the xiphoid process, linea alba and pubic crest.

If you stand up, put your finger on the bony prominence at the side of your hip (your anterior superior iliac spine), run your finger medially and then cough, you can feel the muscle tightening. This is the TvA contracting.

One way to activate the dysfunctional TvA:

- Lie on your back with your knees bent at 90 degrees

- Exhale, contract your abdomen, and pull your belly button towards your spine

- You should be able to feel the muscle contracting if you press two inches in from the bony prominence at the front of your pelvis

- Breathe normally

- Maintain an isometric hold of this position for six to 10 seconds. Release and repeat (15 x 3).

You need to practise this so that you can consciously activate your TvA whenever you are walking, running and, most importantly, doing your exercises. The more you practise doing these activation exercises, the more efficient your brain becomes in instructing these muscles to work – this is what we call an increase in neuromuscular efficiency.

Furthermore, by constantly engaging your core during functional activities, you are able to minimise the adverse effects of certain postural deviations, such as hyperlordosis (lower crossed syndrome) and anterior pelvic tilt.

It is beyond the scope of this article to explore this area in depth, but if you would like any further information, please get in touch.

For more information or advice from Dr Tang, email [email protected].