This month Hannah Hook explores mandible fractures, how to diagnose and work out where the fracture is, as well as how to treat it.

This month Hannah Hook explores mandible fractures, how to diagnose and work out where the fracture is, as well as how to treat it.

Whilst it is unlikely that you will see a patient present with a mandible fracture in general practice, if working in a hospital role you will definitely encounter a few of these.

It is important to understand the signs and symptoms of a mandible fracture. As well as how to assess a patient and the treatment options you can offer.

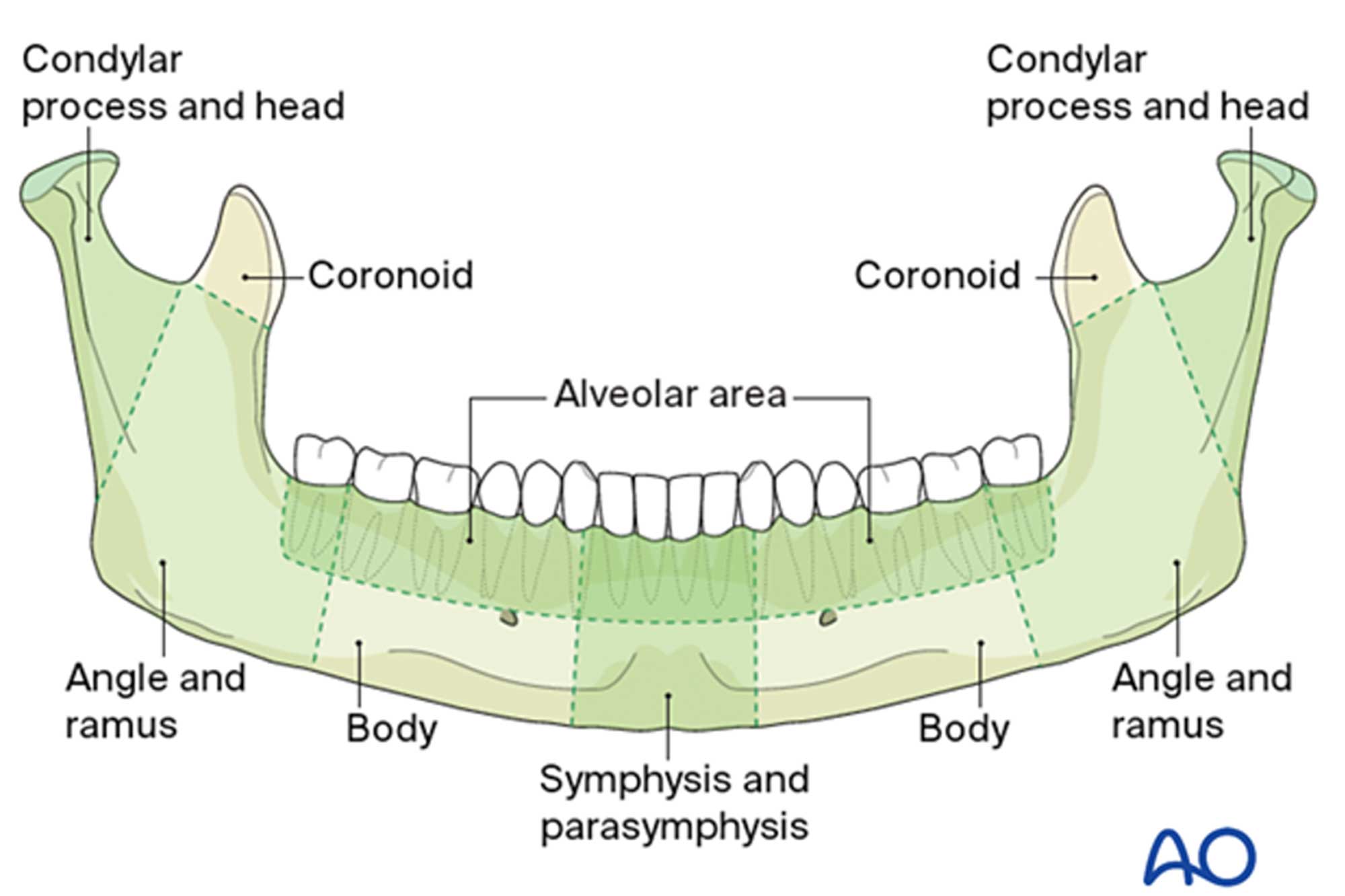

Fracture location

As shown below in Figure 1, there are various locations in which a mandible may fracture. These include:

- Symphysis and parasymphysis

- Body

- Angle and ramus

- Condylar process and head

- Coronoid process

- Alveolar area.

Assessment

- History

- How did it happen? Alleged assault/sports injury/motor accident

- Aetiology may help to indicate fracture type and severity

- Any loss of consciousness? Does the patient need further assessment for a head injury?

- When? Studies have shown that the likelihood of infection at the fracture site decreases the quicker antibiotics are given.

- Physical examination

- Whilst mandible fractures can occur in isolation, more commonly there will be a second fracture bilaterally. It is important to remember this when assessing a patient to make sure a second fracture is not overlooked.

Extraorally

- Assess mouth opening – is it reduced or restricted?

- Palpate TMJ – any pain?

- Palpate along the lower border of the mandible – any bony tenderness or any bony steps palpable?

- Examine mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve – any numbness or altered sensation?

- Deviation of the mandible on opening? This may indicate a condyle fracture

Intraorally

- Any visible soft tissue lacerations? Sublingual haematoma usually indicates an underlying bony fracture

- Any dental trauma? Any missing teeth? Is a chest X-ray required?

- Any changes in occlusion – does the occlusion feel normal for the patient?

- Any step deformity on the occlusion?

- Lacerations or gaps between teeth? Remember to count the teeth, a fracture site may look like a tooth socket!

- Any flexing of the mandible?

- Any loose teeth?

- Two views are required, these are usually an OPG and a PA mandible

- CT scan – usually indicated if fractures are complex or comminuted.

Immediate management

- Immediate management of a patient with a fractured mandible aims to make them as comfortable as possible

- Make sure they are taking regular pain relief

- Carry out bridal wiring of the fracture under local anaesthetic. This can help to approximate the fracture edges, reducing the fracture site and providing stabilisation of the fracture, and therefore improve patient comfort.

To bridle wire a fracture

- Make sure the patient is sufficiently anaesthetised with local anaesthetic

- Using an artery clip a thin piece of wire approximately 0.35-0.45mm passed interproximally between the second nearest tooth to the fracture site, looped around the back of the teeth lingually and passed interproximally between the second nearest tooth on the other side of the fracture site

- The two ends of the wire, which are now buccal, are twisted together and the fracture site will gradually reduce

- Once the fracture is reduced and stabilised as much as possible the free wire is cut off sparing about 5-10mm. This is then curved over to prevent mucosal trauma.

Fracture management

-

Conservative management

Indications

- Single stable undisplaced fracture of the condyle/ramus/angle

- Stable occlusion

- Compliant patient with good oral hygiene.

Management

- No intervention required

- Patient to follow advice below.

-

Surgical management

Indications

- Unstable fracture

- Altered occlusion

- Non-compliant patient.

Management

- Closed reduction (CR): reduce the fracture without having to raise a flap. Use inter-maxillary fixation to approximate the fracture lines. These include archbars and Leonard’s buttons. Elastic bands (like the ones used in orthodontics) may help stabilise the occlusion in the desired position

- Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF): visualise the fracture lines by making an incision into the skin or mucous membrane. Then fix the fracture using metal plates. Close together the skin or mucous membrane flap over the plate

- Following CR or ORIF, the patient still needs to follow the advice below.

Advice

- Regular pain relief

- Antibiotics

- Soft no chewing diet

- Avoiding strenuous or physical activities for six weeks

- Excellent oral hygiene

- Regular chlorhexidine or warm salt water mouth wash

- Regular review with the OMFS department.

Key points

- A thorough assessment of the patient is essential when diagnosing a mandible fracture. This includes history, physical examination and radiographic examination

- Immediate management of the fracture by providing pain relief, local anaesthetic and bridle wiring can help improve patient comfort

- Depending on the type of fracture, clinicians can manage it conservatively or surgically.

Catch up with previous student’s guides:

Follow Dentistry.co.uk on Instagram to keep up with all the latest dental news and trends.