Rizwaan Chaudhary makes the case for amalgam restorations and explains why he thinks it is superior to composites.

Rizwaan Chaudhary makes the case for amalgam restorations and explains why he thinks it is superior to composites.

Make no mistake that for pure aesthetic reasons, composite is still the material of choice due to its shade matching and manipulation.

However, we can also shape amalgam just as well as composites.

There is still some debate with regards to phasing down amalgam. Especially when the Conference of Parties (COP) meet in November this year. Amalgam is listed on the agenda of things to discuss.

The purpose of this article isn’t to discuss the legality of material, yet more as to why I still feel amalgam is needed and how anatomy in the so called metal fillings is achieved.

Currently there are a wide range of courses on composite (whether that is online or hands-on). However, I feel there should be courses available for amalgam restorations. These are the material of choice in NHS settings and in low socio-economic areas.

Why do I prefer amalgam over composite? It’s widely known that amalgam is one of the most versatile materials in dentistry. There is currently no adequate economic alternative (Demarco et al, 2012). Amalgam has a reliable long term performance in load bearing areas, low technique sensitivity, self-sealing property and longevity (Bharti et al, 2010).

Before 1963, amalgams had compositions of low-copper meaning limited life span. They contained gamma-2-phase, which weakened amalgam due to corrosion (Eley, 1997).

Following this, high-copper amalgams were deployed meaning a higher corrosion resistance, increase in longevity and survival rates (Nakai, 1985).

Zinc and copper content of the alloy plays a significant role on the survival rate of amalgam (Bharti et al, 2010).

There are several wide known disadvantages with amalgam, such as unaesthetic appearance, does not chemically bond to the tooth and mercury concerns to name a few (Bharti et al, 2010).

Why amalgam?

Being in a high needs area and working within the NHS setting with limited treatment time, amalgam is still a suitable choice. However my aim now is to ensure every tooth that I restore with amalgam, I shape and carve to ensure it still looks like a tooth.

An intraoral camera is extremely vital. What I’ve realised is that showing the patient what their previous restoration was to what it’s been transformed into leads to a positive reaction.

That we can achieve such aesthetics with a metal filling surprises the majority of patients. And as such, they’re more than happy to continue with metal fillings.

How do I achieve such metal restorations? The key elements are placement, positioning and removing the matrix band.

The positioning of the matrix band is extremely crucial. I don’t tend to over tighten my bands as I feel with this you won’t get a natural curvature of walls.

And burnishing will allow you to ensure you maintain a good contact point.

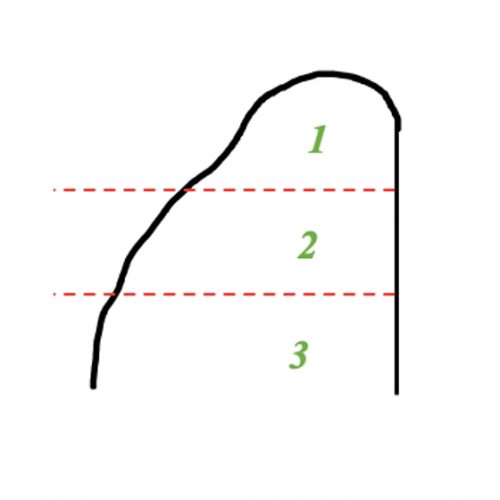

I overpack the cavity with amalgam. This allows easy carving and shaping. When I carve I try to imagine the cusps in three planes as shown below.

If heavy handed when carving and shaping, you risk removing too much amalgam leading to an unnatural shape.

Final touches

Before any shaping and carving, I will remove excess amalgam with a probe 6SE.

For carving and shaping I tend to use Ward Caver 1 and 2. Once I am happy with the shape of cusps, I focus on fissure details. I use probe 6SE to create detailed fissure patterns.

You will naturally start to get fissure patterns when creating cusps. If the restoration includes mesial or distal walls, the natural outline of the marginal wall will start taking shape.

At this stage I will use a Hu-Friedy Burnisher 18 to define the edges and smooth the cusps. Remove the matrix-band carefully along with the wedge.

Once the matrix band is removed I focus on the marginal ridge wall. Ensuring the wall is not high. With the Ward Caver I trim any excess around the marginal ridge.

Finally, I carefully polish the restoration with a Hu-Friedy Burnisher 18. Using a soaked (in water) cotton wool pledget, I’ll give the restoration a final wash to remove any excess amalgam.

My personal view is that we still need amalgam. It is a material that can look beautiful. Clinicians require delicate hands and time. But carried out correctly, the longevity of the material is second-to-none.

References

Bharti R, Wadhwani K, Tikku A and Chandra A (2010) Dental amalgam: An update. Journal of Conservative Dentistry 13(4): 204

Demarco F, Corrêa M, Cenci M, Moraes R and Opdam N (2012) Longevity of posterior composite restorations: Not only a matter of materials. Dental Materials 28(1): 87-101

Eley B (1997) The future of dental amalgam: a review of the literature. Part 1: Dental amalgam structure and corrosion. British Dental Journal 182(7): 247-9

Nakai H, Suzuki K and Hashimoto H (1985) Effect of Mercury to Alloy Ratio on the Hardness of Low and High Copper Amalgams. Dental Materials Journal 4(2): 125-33