Juergen Manhart and Hubert Schenk present a full ceramic crown case after a complicated fracture of an anterior tooth.

In the maxillary anterior region, the integrity of the teeth is of great importance to most people. In case of damage, therefore, restoring an attractive smile is a great need for patients.

For heavily damaged anterior teeth, all-ceramic crowns are a reliable and proven therapy option for restoring function and aesthetics.

Initial situation

A 24-year-old female patient presented in our dental clinic with a trauma-related fractured right maxillary central incisor.

The accident had already occurred one week earlier abroad, where the patient (medical student) was in the context of a clinical traineeship.

Since the collapse occurred in a developing country with medical and dental treatment localities not corresponding to modern standards, the patient decided – after the initial treatment of soft tissue injuries on the spot by a fellow student (Figure 1) – to cancel the stay abroad for the dental therapy, because she preferred a treatment in a familiar environment according to modern standards.

During the examination in our clinic, one week after the incident, the patient presented a still untreated trauma-injured tooth UR1 (Figures 2a and b).

The clinical inspection showed a complicated crown fracture with exposure of the pulp (Figure 3), the incisal half of the clinical crown had been completely lost.

Patient assessment revealed a sharp painful response to cold thermal stimulus using refrigerant spray and a pathologic response to percussion of the respective tooth.

The pulp had already been exposed to the oral cavity environment for one week, the tooth showed unprovoked pain symptoms and root growth was complete; thus, we decided together with the informed patient, to completely remove the infected pulp with subsequent root canal treatment (Figure 4).

Treatment planning

The patient was informed about various therapeutic approaches (direct composite restoration, ceramic veneer, full ceramic crown, PFM crown) including their respective advantages and disadvantages and associated costs.

The patient decided in favour of an adhesively luted glass ceramic crown made of veneered lithium-disilicate ceramics.

This restoration type can be recommended as evidence-based treatment in the anterior region.

In the literature, survival rates of between 93.8% and 96.8% are reported at five, eight or 10-year observation periods.

After completion of the root canal treatment, a long-term provisional build-up of the tooth was carried out with an adhesive direct composite restoration (Figures 5a and b) in order to spare the patient a preparation and impressions until the soft tissue situation had completely healed.

After a waiting period of three months, a new clinical examination was carried out, in which the tooth UR1 and its adjacent teeth, including the antagonists in the lower jaw, were inconspicuous (Figure 6).

The patient was asked to present herself the next day for shade determination and in general for dental aesthetic analysis in the dental laboratory.

A basic requirement for accurate colour determination is that the teeth are not dehydrated, otherwise they appear lighter and more opaque.

Aesthetic analysis

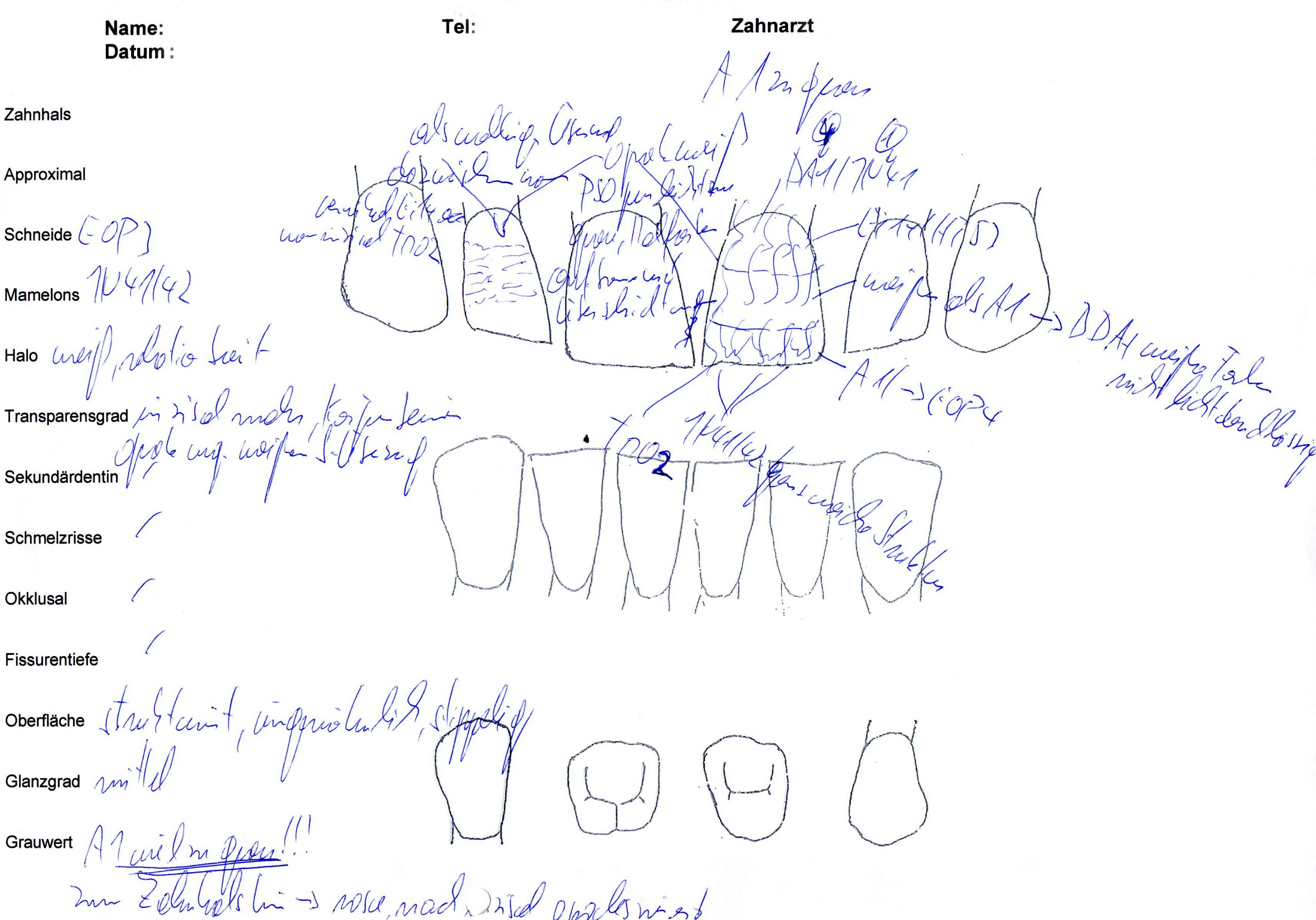

As part of the aesthetic analysis by the dental technician, the distribution of the different shades of colour and translucent or opaque tooth areas in the area to be restored is determined (Figures 7a to b).

The age-appropriate design of the restoration with corresponding individual characteristics (eg enamel cracks, white spots, mamelons, halo effect), the appropriate surface texture and the correct gloss level are also analysed.

In principle, during the dental aesthetic analysis by the ceramist technician, a ‘virtual layering’ of the restoration is carried out, with determination of the necessary ceramic masses.

The result of this ‘virtual layering’ is recorded in the ceramic buildup scheme (Figure 8).

This procedure is carried out on site in the dental laboratory under ideal lighting conditions – which are often not found in dental practices – by the ceramist technician, who will ultimately also fabricate the restorations.

Preventing communication breakdowns

If the colour analysis is performed directly by the dental technician and not by the dentist or other practice staff, there is usually no misunderstanding and the responsibilities for this important aspect in the treatment process are clearly assigned.

Such a procedure eliminates the risk of communication breakdowns and prevents valuable time being spent at the dentist’s chair on this sometimes longer-lasting and, from the dentist’s point of view, unproductive step.

Only the direct contact with the patient enables the dental technician to produce an aesthetically perfect matching ceramic crown.

It is optimal if this analysis is performed before treatment starts.

This allows the dental technician to get his own impression of the initial situation and also to query unfiltered the patient’s expectations of the new restorations.

A patient-specific optimal tooth position and shape of the restoration is sought.

Implementation of the individual functional and aesthetic optimum for each patient thus requires close collaboration with the specialised dental technician from the beginning of the planning phase.

The independent aesthetic analysis of the intraoral situation by the ceramist is thus a basic requirement for success.

Tooth preparation

In the next appointment, the tooth UR1 was prepared for a full ceramic crown with a circumferential shoulder with rounded inner edges (Figure 9).

The strength of all-ceramic restorations is determined by the type of ceramic used with the resulting inherent mechanical stability of the respective ceramic material.

Furthermore, the fracture strength is determined by the geometry of the restoration and thus by the shape of the cavity or crown preparation.

The basic principle of preparation design for all-ceramic restorations avoids tensile stresses in the material as much as possible and loads the restoration primarily in compression mode by an adequate preparation geometry.

Fracture strength of the restorations is determined by size, volume, shape and surface characteristics of the ceramic material and additionally by structural inhomogeneities introduced during the manufacturing process.

The dentist must be aware of the fact that the shape and finish of the tooth preparation have a major impact on the clinical success and longevity of all-ceramic restorations.

Crown planning

The preparation should exhibit a retention form and resistance form optimal for a ceramic crown:

- Height of prepared tooth (abutment height) minimum 4mm

- Occlusal convergence angle between 6 and 10 degrees

- Finish line: circumferential shoulder with rounded inner edges or obvious deep chamfer with 1mm width

- Incisal/occlusal reduction of 1.5-2.0mm (adhesively luted full contour lithium-disilicate crown: minimum 1.0mm)

- Axial reduction depth (sufficient circular crown thickness) of 1.2-1.5mm

- In the anterior region: a rounded incisal edge

- Rounded internal line angles and point angles

- Smooth surface texture.

Tooth substance removal was controlled in all dimensions.

Attention was paid to the possibility of a sufficient palatal layer thickness of the crown framework to be produced, even in positions that the tooth occupies – in addition to the static occlusion – in dynamic occlusion (Figure 10).

After tooth preparation

During the fabrication of highly aesthetic restorations, the influence of the shade of the prepared tooth on the final result is a decisive aspect.

After finishing the crown preparation, the shade of the prepared tooth substance was documented by the dentist with a digital photo referencing to a special shade guide (IPS Natural Die Material shade guide, Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein).

The image file was then made available electronically to the dental laboratory.

This enables the technician – who otherwise has no information about the colour of the tooth stump – to fabricate a model die similar in colour to the prepared tooth of the patient, on the basis of which the correct shade, translucency and brightness values of the all-ceramic restoration may be selected.

In order to achieve a perfect impression, the marginal gingiva was displaced by insertion of a retraction cord to the sulcus (Figure 11).

After taking impressions of the prepared tooth and the antagonistic dentition, an occlusion protocol with Shimstock foil was made, as well as intermaxillary registration by fabricating an interocclusal record in maximal intercuspal position and arbitrary transfer of the maxillary position using a facebow record was performed.

A diagnostic template made from a gypsum duplicate of the analytical wax-up using a transparent polyethylene foil allows the chairside fabrication of a direct provisional restoration with correct dimensions and alignment (Figure 12a).

The provisional was seated using an eugenol-free temporary cement (Figure 12b).

Laboratory work

In the dental laboratory, the ceramic crown for tooth UR1 was produced.

For this purpose, a crown framework made of lithium-disilicate-reinforced high-strength glass ceramic was pressed corresponding to the anatomically correct shape of the respective tooth (Figure 13a).

This coping was subsequently finalised by individual veneering with layered porcelain (presslayer technique) (Figures 13b to 3).

Try-in and adhesive luting procedure

One week after taking impressions, the final appointment was scheduled.

After removal of the provisional restoration and cleaning of the tooth with a rotating brush and fluoride-free prophylaxis paste, the gingiva presented in a healthy condition (Figure 14).

Using coloured, glycerin-based, try-in pastes, the aesthetics of the ceramic crown was checked intraorally with reference to hydrated adjacent teeth and the correct shade of the luting resin was determined.

Subsequently, the precise fit of the crown on the prepared tooth and quality of proximal contacts were checked before minor functional interferences during protrusive and laterotrusive movement paths were eliminated.

The method of cementation of the crown to the prepared tooth was by adhesive luting, as opposed to conventional cementation.

This gives a positive effect on the overall strength of the restoration, in particular for glass ceramic materials, which are more prone to bulk fracture and chipping effects than zirconia.

Cementation

Ceramic materials with fracture strength less than 350MPa are not indicated for conventional cementation.

Among those are feldspathic porcelains and leucite-reinforced glass ceramics that have to be placed adhesively using bonding agents and luting resins.

Due to the adhesive bond between the ceramic restoration and enamel or dentine, a considerable increase in strength can be obtained because the inner surface of the ceramic restoration no longer acts as a mechanical boundary line at which fracture causing cracks can initiate due to tensile stresses.

The adhesive cementation of ceramic restorations is a very technique-sensitive procedure.

In order to achieve a reliable and long-lasting bond to the tooth structures, it is of utmost importance to prepare this step carefully and to observe the cementation protocol.

Luting

Prior to the luting procedure, the marginal gingiva was displaced to expose the complete shoulder using a retraction cord (Figure 15).

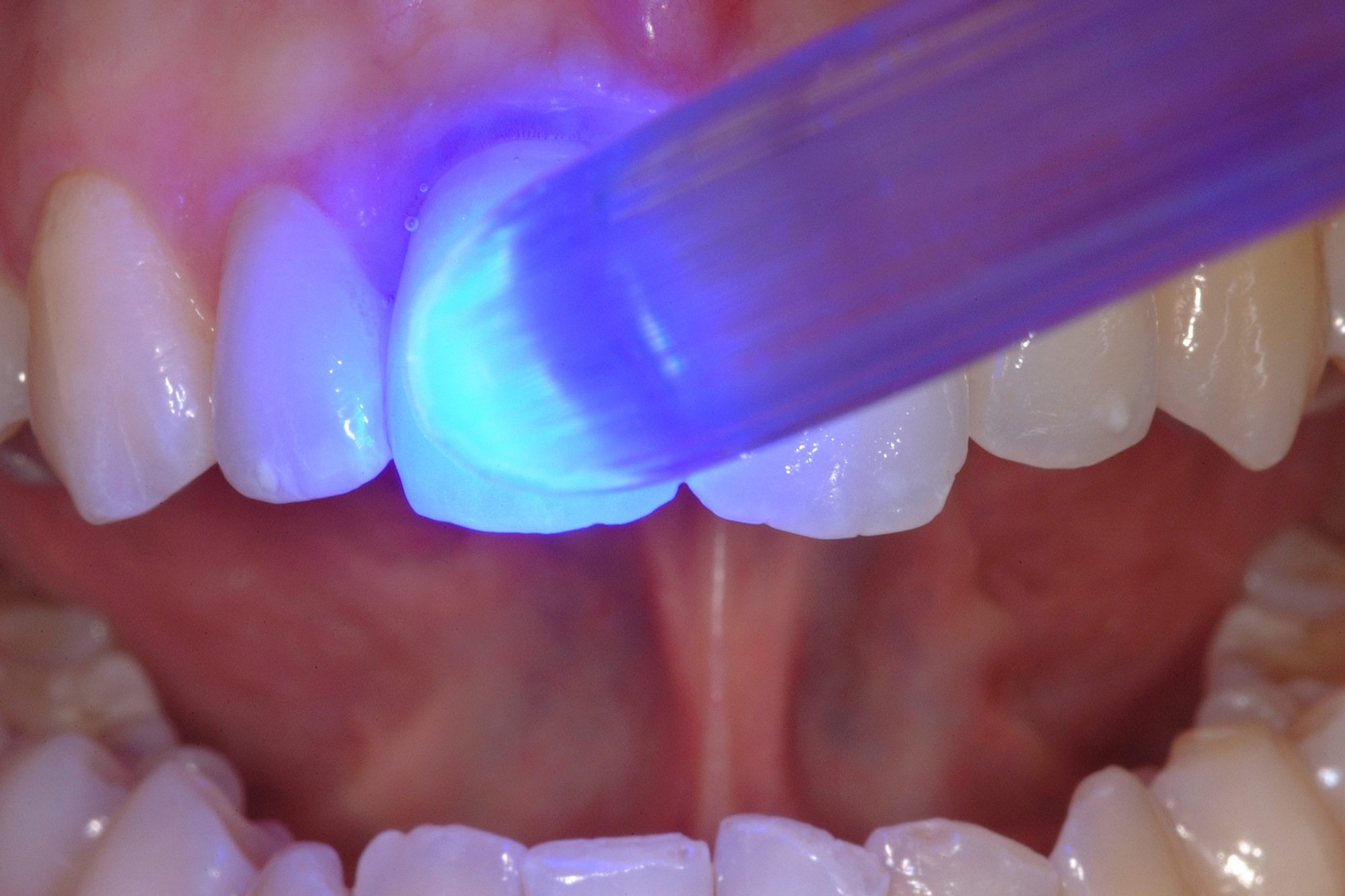

Afterwards, the inner surfaces of the lithium-disilicate glass ceramic crown were etched with hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds (Figure 16).

After thoroughly rinsing and drying the crown, the fitting surfaces were silanised (Figure 17).

After adhesive pretreatment of the prepared tooth by conditioning enamel and dentine with 37% phosphoric acid (Figure 18) the tooth was thoroughly rinsed with water-spray and air-dried.

An adhesive was applied meticulously on all surfaces (Figure 19a).

After the correct exposure time, the bonding layer was air-thinned and the solvent was evaporated carefully with compressed air (Figure 19b).

The ceramic crown was adhesively luted by covering its intaglio surfaces and the prepared tooth both with dual-curing resin cement in the previously determined shade and the restoration was positioned on the tooth with light finger pressure (Figure 20).

Post-placement

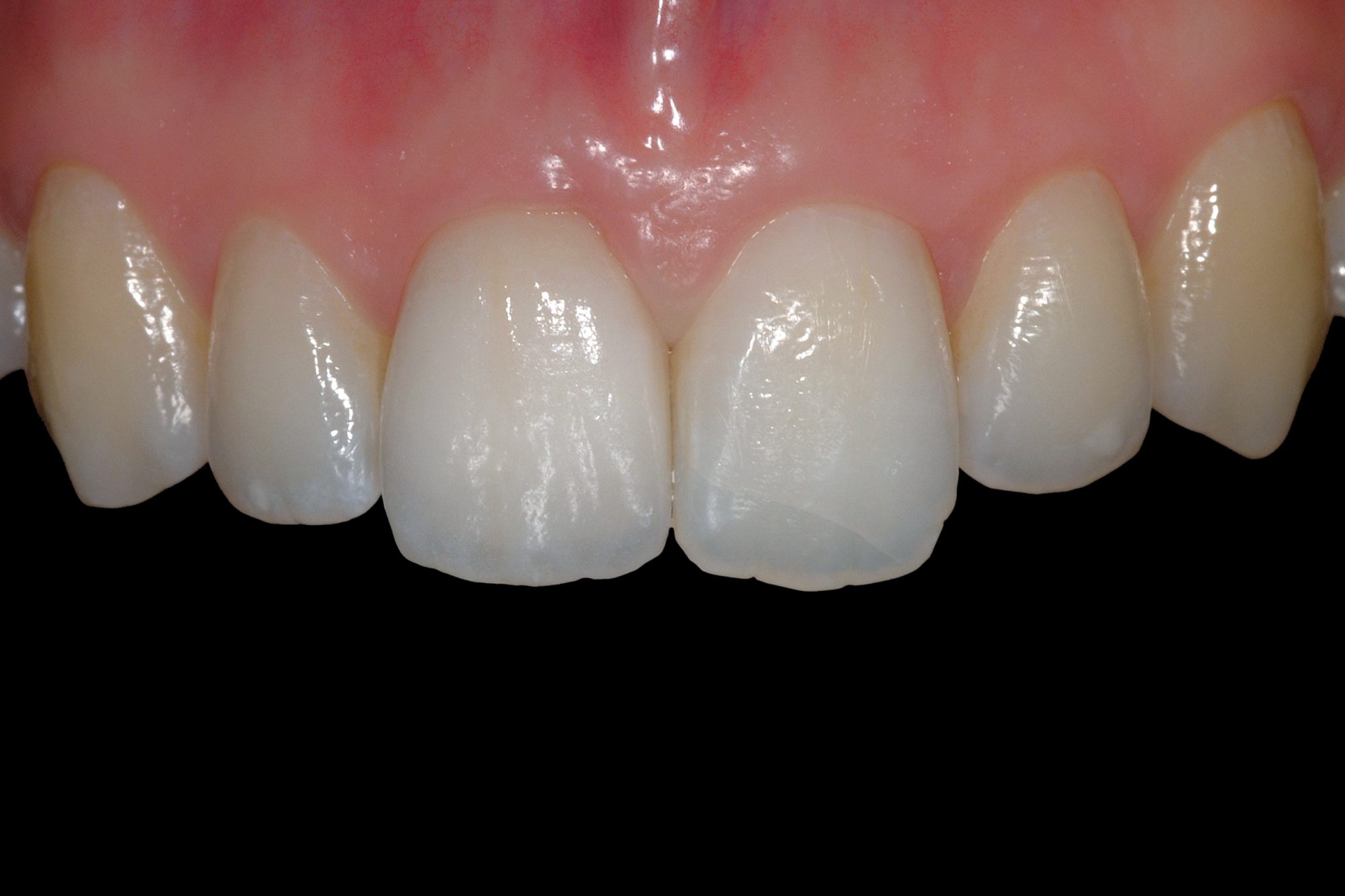

Two weeks after placement, the restoration exhibited an optimal functional and aesthetic integration into the neighbouring teeth (Figure 21).

Background illumination demonstrates the excellent light transmittance capacity of the glass ceramic crown, which impresses by having virtually the same optical properties as the surrounding natural dentition (Figure 22).

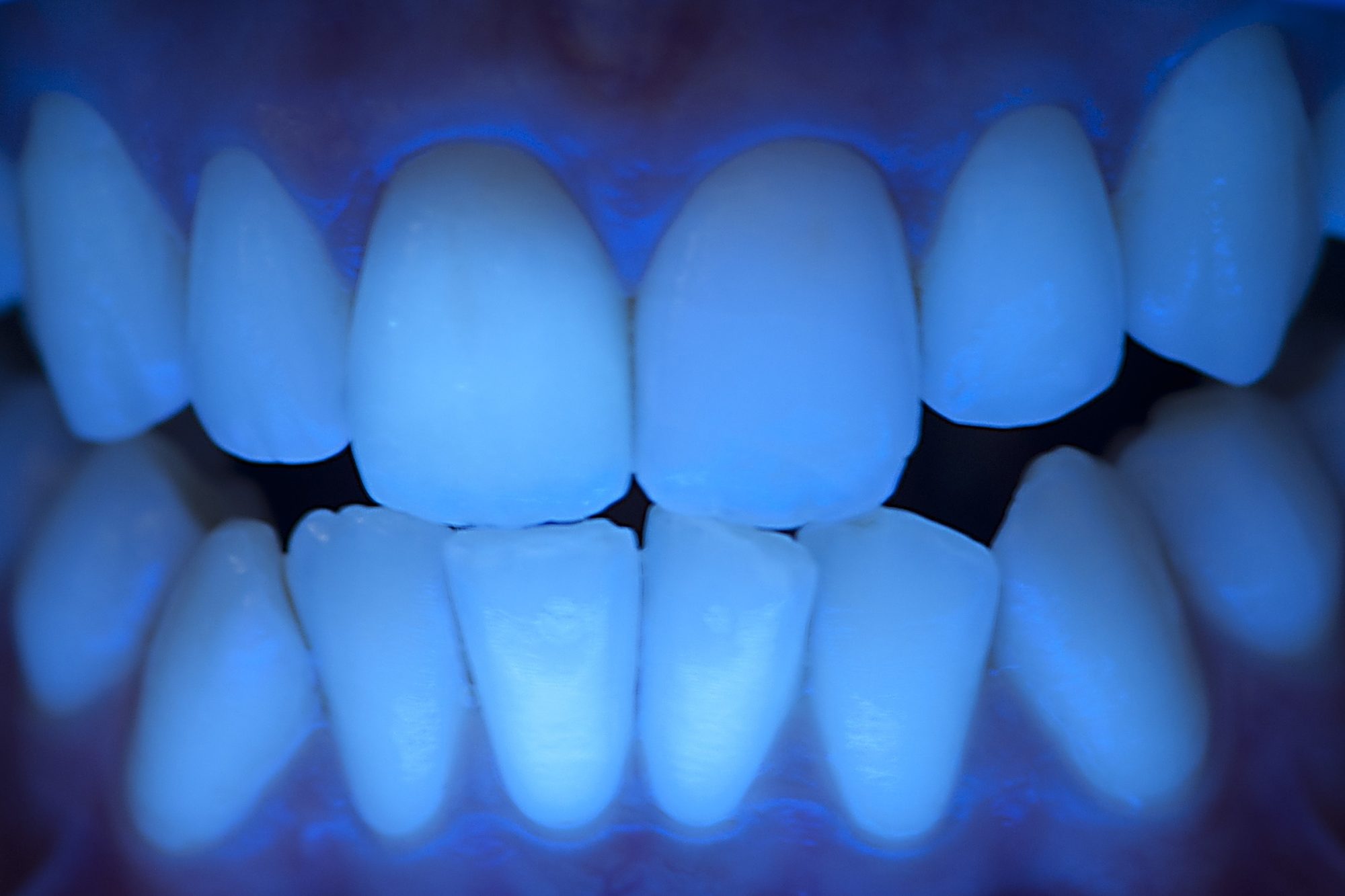

Ultraviolet light activates the inherent fluorescence properties of the restoration, which are equal to natural tooth structure (Figure 23).

Silicate ceramics exhibit translucency effects and light-optical properties that are comparable to natural hard tooth substance, making them ideal for fabricating restorations that have to meet highest aesthetic demands.

The light scattering of silicate ceramics also supports a natural vital appearance of the adjacent gingiva.

The difference to this ‘pink aesthetics’ becomes clear in comparison with metal-supported restorations, which block this light conduction towards the marginal soft tissue and often cause a grayish shading on the marginal gingiva.

At the end of the successful treatment, the patient’s smile was no longer compromised (Figure 24).

Five years after adhesive cementation of the ceramic crown, there is still an excellent integration in the surrounding teeth, both in habitual intercuspation and in dynamics (Figures 25a to b).

The crown still harmonises in dialogue with the lips.

Finally, the patient thanks the treatment team with a happy smile (Figure 26).

Conclusion

All-ceramic restorations have achieved an excellent quality and are an indispensable therapeutic means for modern conservative and prosthetic dental treatment procedures.

Aesthetics and biocompatibility characterise these restorations.

At the same time, this type of restoration achieves excellent patient acceptance.

Clinical trials exhibit an excellent longevity for all-ceramic restorations if a correct indication is selected and material and patient-related limitations are observed.

Follow Dentistry.co.uk on Instagram to keep up with all the latest dental news and trends.