Eduardo Anitua presents a case that explores the role of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of a lingual nodular lesion.

Eduardo Anitua presents a case that explores the role of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of a lingual nodular lesion.

Granular cell tumour (GCT), previously known as granular cell myoblastoma (as it was wrongly assumed to be derived from muscle cells), was first described in 1926 by Abrikossoff. Therefore, this tumour is also known by his name (Barca et al, 2020).

GCT is a soft tissue tumour of unknown cause, now considered to be derived from Schwann cells (Pantaleo et al, 2014).

It can present at any part of the body, although most cases are located in the head and neck region. Within this area, the most frequent location is the tongue, both in the dorsum or in the margins (Barca et al, 2020, Pantaleo et al, 2014).

GCT is more common in women and can occur at any age, being more frequent between the fourth and sixth decade of life.

Nevertheless, cases in young patients have also been reported (Daniels et al, 2009; Giuliani et al, 2004; Eguia et al, 2006).

Most cases of GCT on the tongue (48%) are located on the dorsum, and present as a hard or elastic consistency superficial nodule, generally mobile (Eguia et al, 2006; Suchitra et al, 2014; Becelli et al, 2001; Sena et al, 2012; Dive et al, 2013; Rivas et al, 1996; López-Jornet et al, 2008).

The size normally ranges between 2cm and 5cm and the overlying mucosa may show a normal appearance or a slight depapilation (Eguia et al, 2006; Suchitra et al, 2014; Becelli et al, 2001; Sena et al, 2012; Dive et al, 2013; Rivas et al, 1996; López-Jornet et al, 2008).

Treatment is based on the complete excision of the lesion.

Most GCTs are benign and local recurrence is uncommon (Marcobal et al, 2020).

Clinical case

A 32-year-old male patient presented at the clinic with a painless nodular lesion incidentally discovered on the dorsum of the tongue.

The patient appeared to be in the overall good health and smoked 15 cigarettes per day.

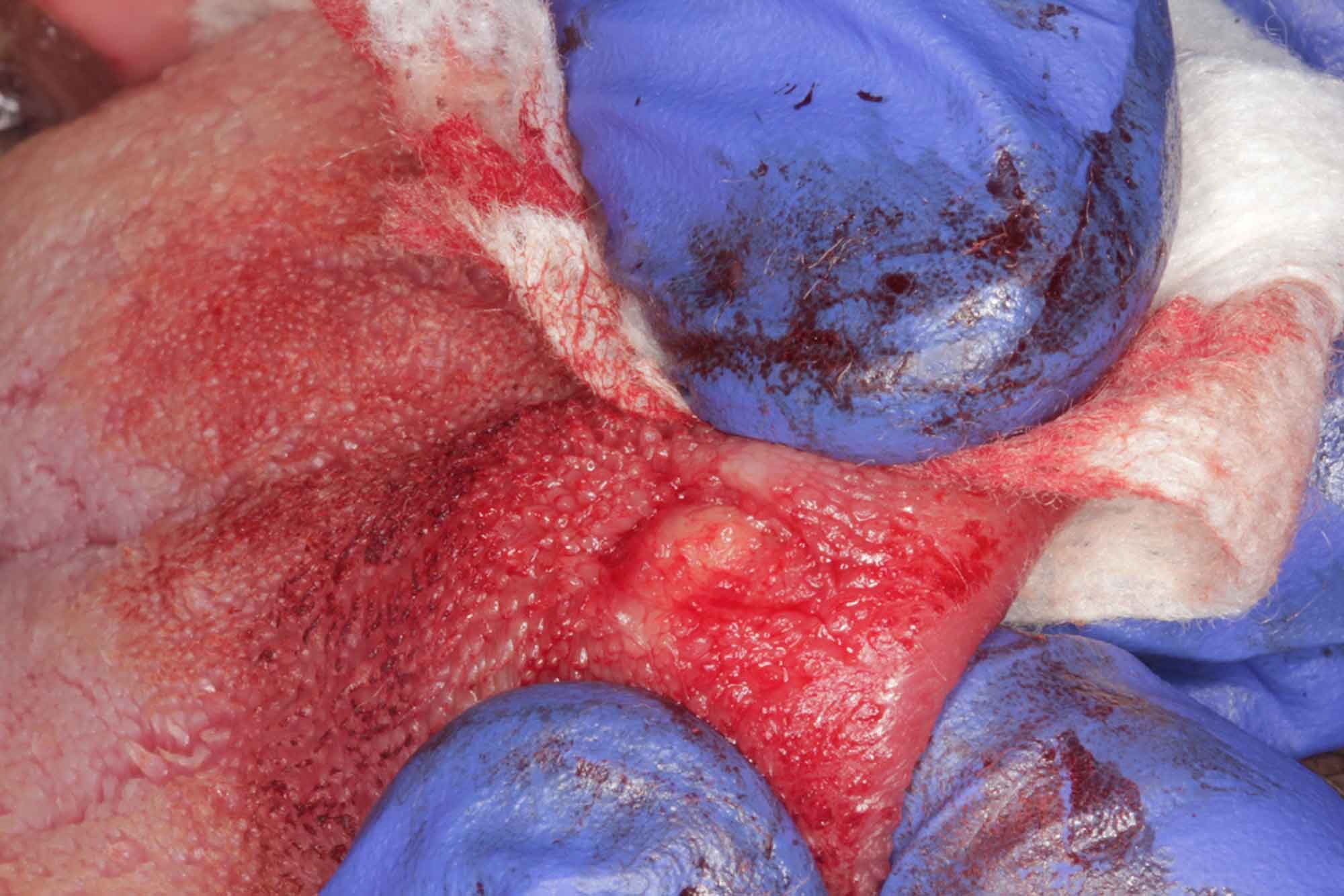

An intraoral examination revealed a mobile roundish firm nodule in the thickness of the dorsum of the tongue, located in depth.

On the surface of the lesion a slight depapilation could be observed. The patient referred the habit of rubbing the superficial area of the lesion with the upper incisors (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history stated that he had undergone surgery for several epidermoid skin cysts and that the dermatologist who had treated him pointed to another similar lesion as a possible cause of the lingual nodule.

Given the location of the lesion, the clinical examination and the absence of associated symptoms that could guide the diagnosis, an excisional biopsy was performed followed by histopathological examination.

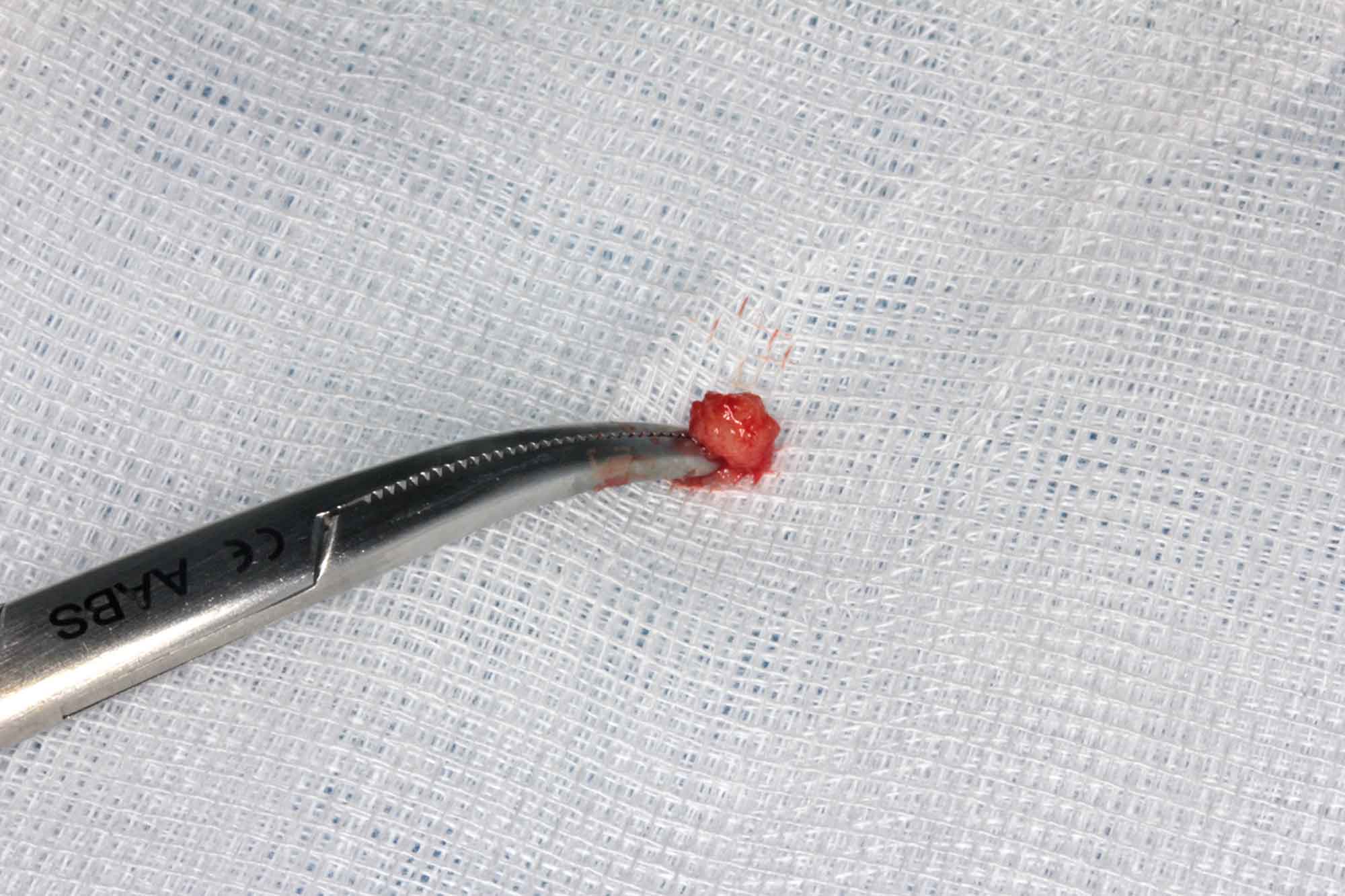

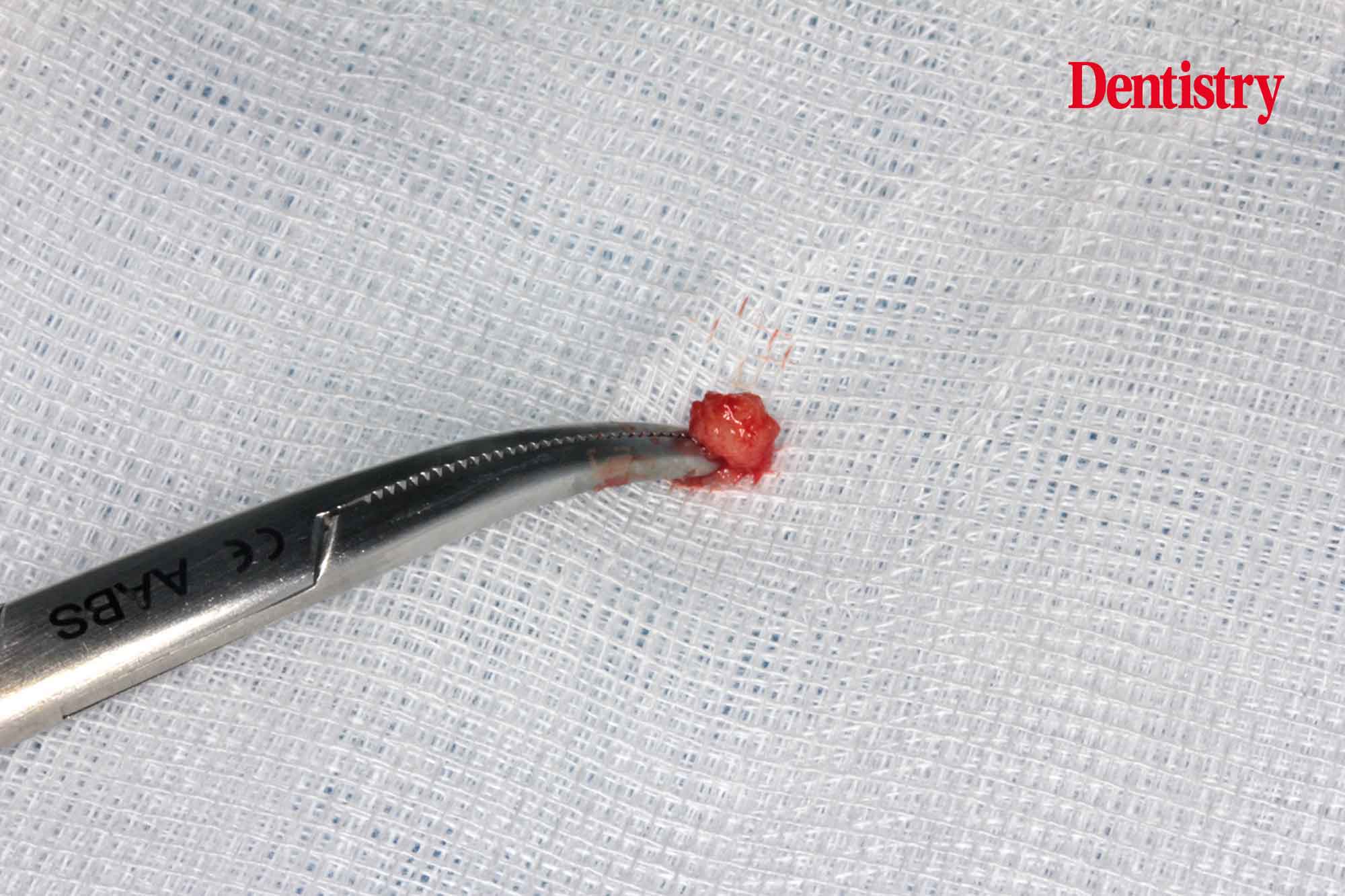

After an incision on the dorsum of the tongue, a blunt dissection was performed to locate the mass and enucleate it through the incision (Figures 2 to 4). Once removed, the lesion was sent for histopathological analysis in a 10% buffered formalin solution to the oral and maxillofacial pathology diagnostic service of the University of the Basque Country.

Possible diagnosis

As can be seen in Figures 6 and 7, the tumour was 5mm in its largest diameter, and had a rounded morphology.

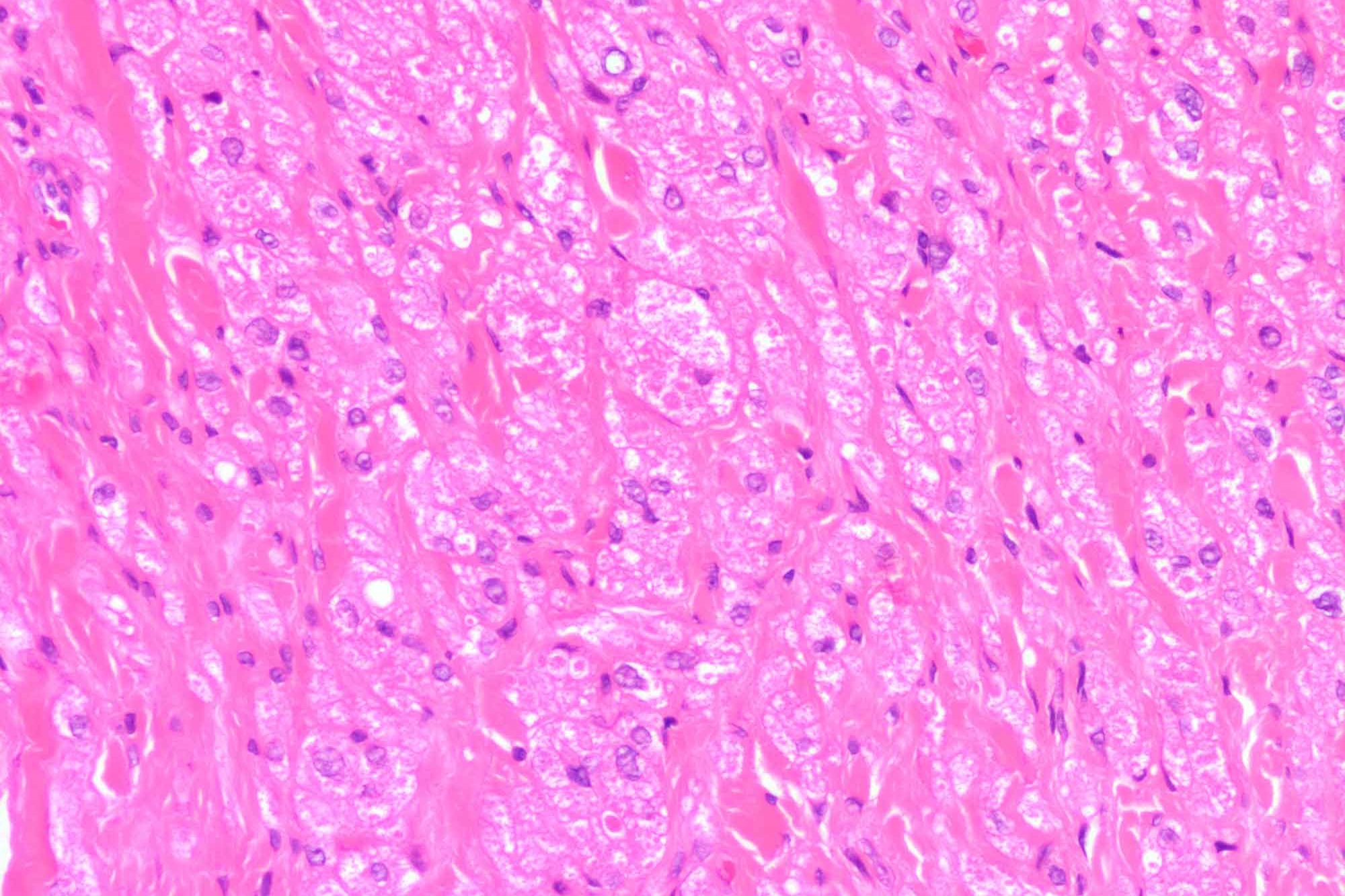

The haematoxylin-eosin staining revealed the presence of rounded cells with a central vesicular nucleus (Figure 8). The cytoplasm of these cells was eosinophilic and showed granulations in the form of inclusions.

Due to the presence of these cells with a granular appearance, suggesting a possible diagnosis of GCT, staining with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) was performed.

PAS staining was positive for the granules observed in the cytoplasm (Figures 9).

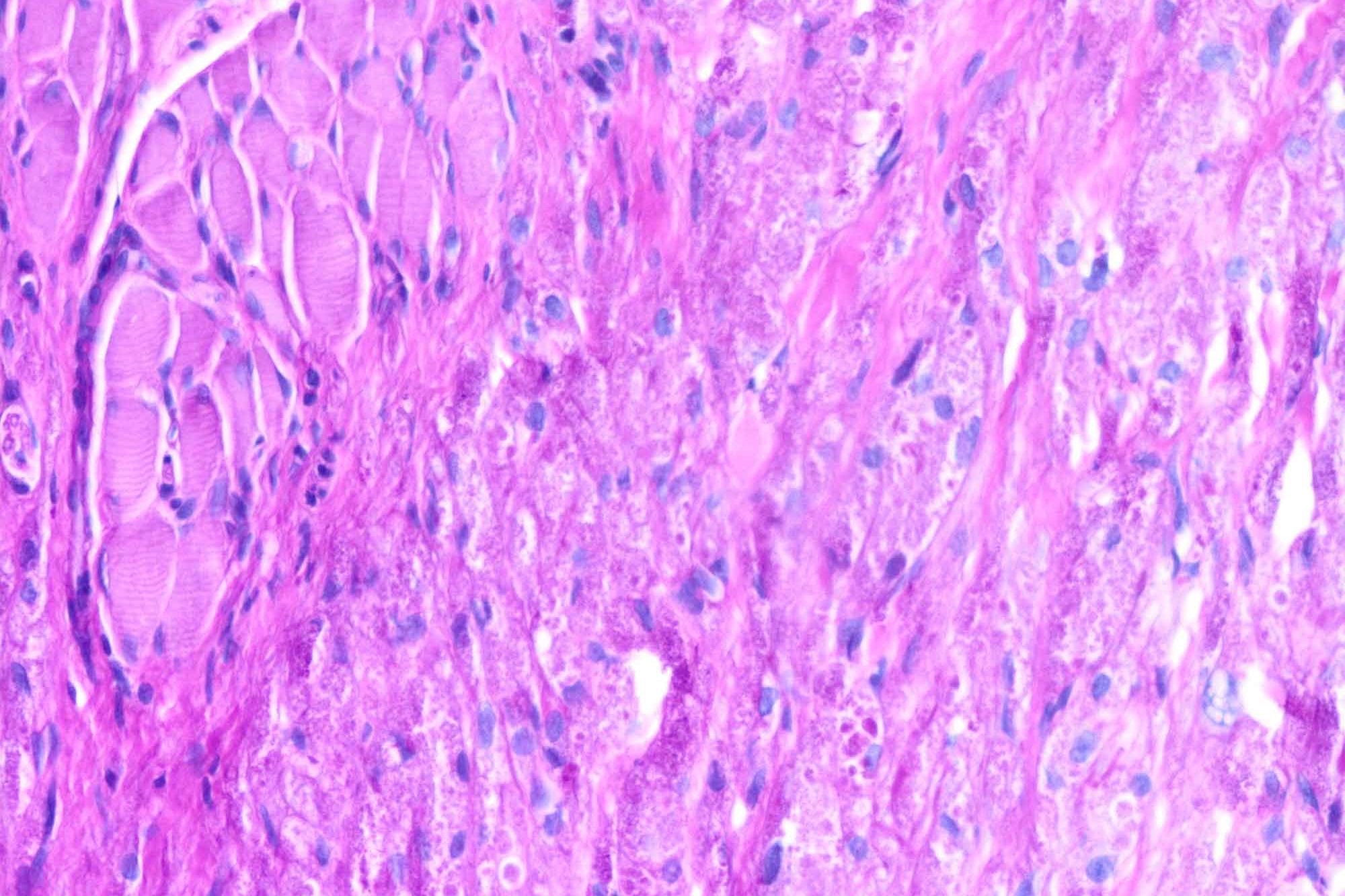

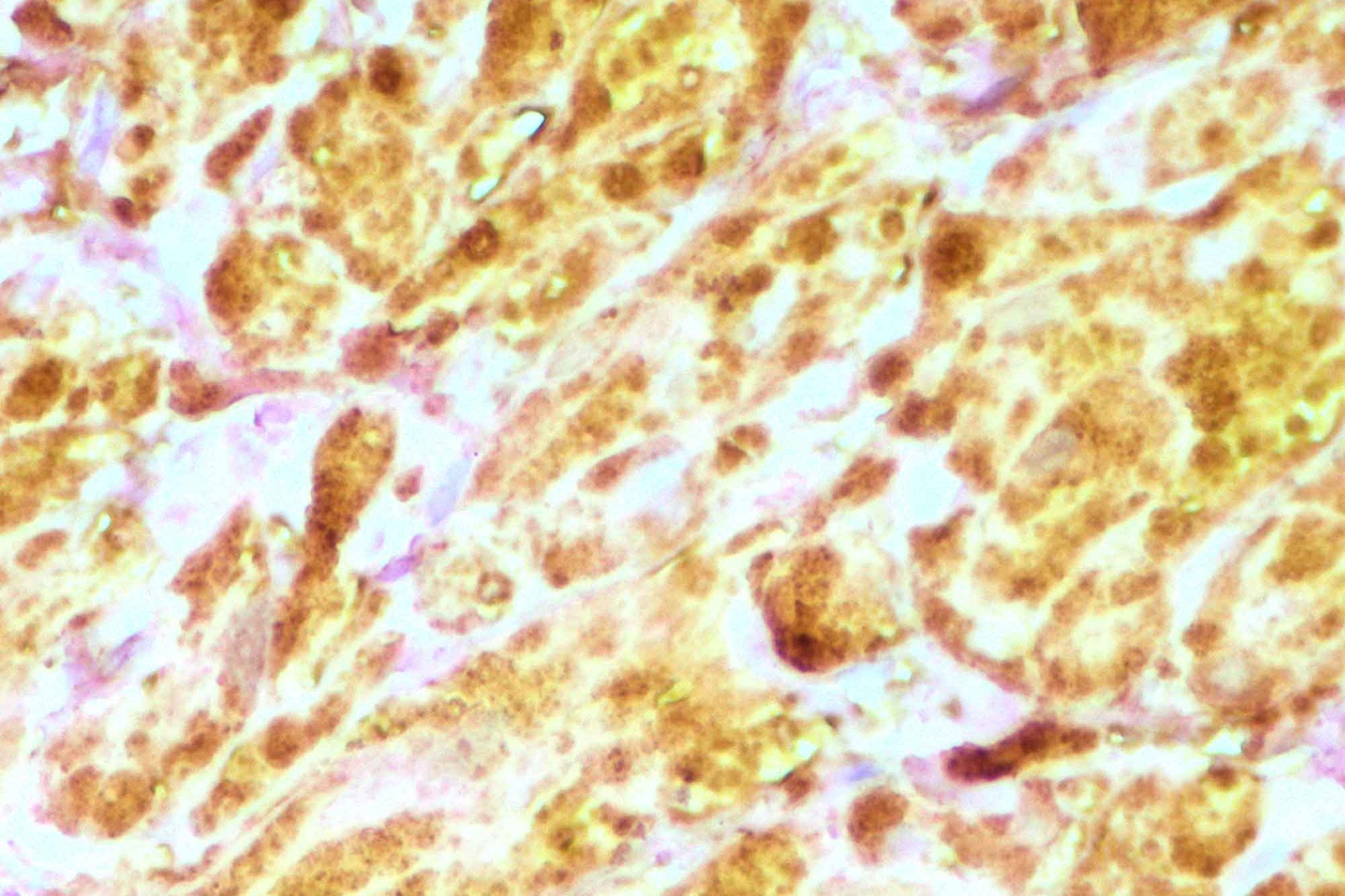

To confirm the diagnosis, an immunohistochemistry analysis was also performed. A high positivity for S-100 protein was observed.

Based on the clinical and histological characteristics of the lesion, a final diagnosis of GCT was stablished. Once the tumour was removed, the patient attended to regular check-ups without any recurrence of the tumour after one year of follow-up.

Discussion

GCT is an uncommon tumour, frequently presenting as a firm sub-epithelial nodule on the lingual dorsum, in cases of oral location (Eguia et al, 2006; Suchitra et al, 2014; Becelli et al, 2001; Sena et al, 2012; Dive et al, 2013; Rivas et al, 1996; López-Jornet et al, 2008; Fronie et al, 2011; Labayle et al, 1969; Han et al, 2016; Rogers et al, 2004; Budi et al, 2003).

Despite the different hypotheses about its origin, the positivity for S-100 in immunohistochemistry would indicate a neural origin, probably from Schwann cells (Budi et al, 2003; Torrigos-Aguilar, 2009).

In most cases of GCT in the oral cavity, the aetiopathogenic mechanism is unknown (Becelli et al, 2001).

In the anamnesis of some patients, as in our patient, there was a history of chronic trauma and pressure of the teeth on the tongue, although GCT is not considered to be a reactive type of lesion (Becelli et al, 2001; Sena et al, 2012; Dive et al, 2013).

In some lingual GCTs, as in the case we present, depapilation and/or atrophy of the mucosa over the tumour can be observed (Becelli et al, 2001; Sena et al, 2012; Dive et al, 2013).

Differential diagnosis

This clinical finding could be helpful in the differential diagnosis with other nodular lesions on the tongue in which this phenomenon is not frequently observed.

The definitive diagnosis of GCT must be based on clinical and histological findings. A PAS staining and immunohistochemical markers such as S-100 and sometimes CD-57 are necessary to confirm the diagnosis (Merelo et al, 2011; Plan et al, 2013; Vera-Sempere et al, 2003; Martinez-Estrada et al, 2014; Martinez-Estrada et al, 2014).

Even in more complex cases, vimentin and leu-7 may also help to reach the definitive diagnosis (myelin-associated glycoproteins) (Merelo et al, 2011; Plan et al, 2013; Vera-Sempere et al, 2003; Martinez-Estrada et al, 2014; Martinez-Estrada et al, 2014).

In the histological study, signs of malignancy should also be analysed, as there are reported cases of malignant variants and co-existence of GCT and squamous cell carcinoma (Naief et al, 1997).

Naief et al (1997) found the association of this type of tumour with squamous cell carcinoma in 13 cases, and isolated cases have since been reported in other articles (Caroppo et al, 2018; Son et al, 2012; Bedir et al, 2015).

In this sense, the presence of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be a confounding factor in the diagnosis of this circumstance (Son et al, 2012; Bedir et al, 2015). Surgical excision is the most accepted treatment for this type of tumour.

A wide safety margin is required in cases where malignancy is suspected (Budi et al, 2003; Torrigos-Aguilar, 2009). In all cases, once the lesion has been removed and analysed, the patient should be periodically followed-up, as although it is not frequent, cases of recurrence have been described (Barca et al, 2020; Pantaleo et al, 2014).

Conclusion

GCT is an uncommon tumour but it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of lingual nodular lesions. The final diagnosis should include immunohistochemistry to identify the origin of the lesion and to stablish the definitive diagnosis.

For a list of references, please contact [email protected].

This article was first published in Clinical Dentistry magazine. Sign up to receive Clinical Dentistry magazine here.