November is Oral Cancer Awareness Month. Hannah Hook explores the journey of a patient with oral cancer and how the GDP can help.

November is Oral Cancer Awareness Month. Hannah Hook explores the journey of a patient with oral cancer and how the GDP can help.

The initial diagnosis of ‘cancer’ represents a brief moment in time with a monumental impact on a patient’s future; ultimately changing their life forever.

Whilst relatively rare, oral cancer accounts for 2% of all cancers. With 8,722 people diagnosed each year in the UK.

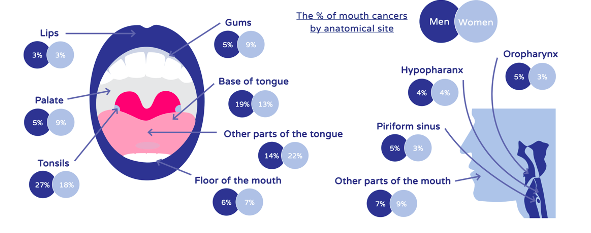

Of all cases, 34% occur in the tongue (Figure 1) and 90% are squamous cell carcinomas.

Despite 46% of cases being preventable, mortality rates have increased 16% in the last decade. Although incidence rates remain highest in those aged 55-74, the demographic is gradually changing. With an increased occurrence in both patients under the age of 45 and in females (Scully and Kirby, 2014).

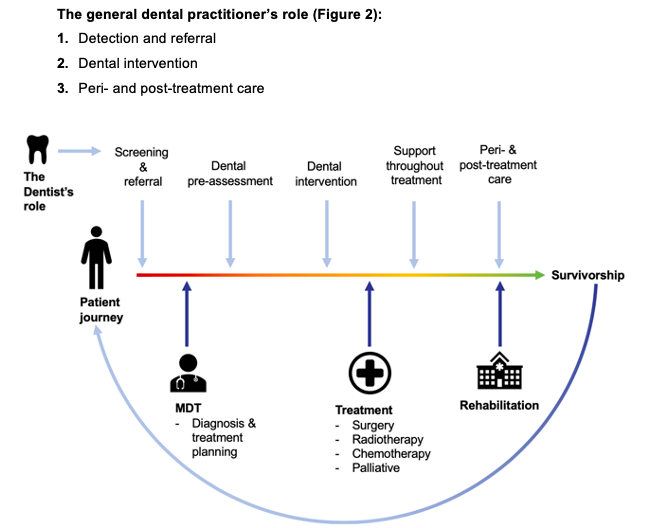

From a patient’s diagnosis to the delivery of their oral treatment, each member of the dental team plays a vital role and can have a positive impact on the patient’s quality of life.

Often, both in undergraduate and postgraduate training, the focus surrounds developing skills in the prevention and detection of oral cancer. This can sometimes overshadow the importance of the holistic management of the patient. Not just at the time of referral, but prior, peri- and post-treatment (Beacher and Sweeney, 2018).

It is essential that a collaborative approach is adopted by the dental team in order to focus on the provision of the most efficient and effective care possible.

1. Detection and referral

A general dental practitioner (GDP) is often the first person to detect signs of oral cancer. In comparison to many other sites, the oral cavity is readily accessible to thorough examination (Macpherson et al, 2003).

The cornerstones of early detection include regular oral cancer screenings with each check-up. Coupled with thorough history taking to clarify any risk factors the patient may have that predispose them to oral cancer (Beacher and Sweeney, 2018).

Alongside this is the ability to recognise signs and symptoms. And to understand the various presentations of oral cancer, shown in Table 1. These may warrant an urgent two-week referral.

Taking immediate action is key to ensuring the best outcome possible for the patient.

Early detection of oral cancer is pivotal. With the stage at which the cancer is diagnosed having a significant impact on the chances of survival and reducing morbidity (Scully and Kirby, 2014; LeHew et al, 2010).

The burden of any head and neck cancer is vast. With later stage diagnosis entailing debilitating treatment, prolonged rehabilitation and decreased survival rates (Figure 3).

| Symptoms | |

| Extra oral | Persistent unexplained head and necks lumps >three weeks |

| Persistent hoarseness >three weeks | |

| Ear pain without evidence of local abnormalities | |

| Cranial neuropathies | |

| Orbital masses | |

| Solitary nodule increasing in size | |

| Intraoral | Ulceration or unexplained swelling of the lip or in the oral cavity >three weeks |

| All red/white or mixed read and white patches of the oral mucosa consistent with erythroplakia or erythroleucoplakia >three weeks | |

| Dysphagia or odynophagia >three weeks | |

| Pain in the throat lasting >three weeks | |

| Unexplained tooth mobility not associated with periodontal disease | |

Table 1: Table displaying the NHS (2019) criteria for two-week wait cancer referral

2. Dental interventions

Once a diagnosis of oral cancer is confirmed, the patient’s case is presented to a multidisciplinary team (MDT). This team comprises the maxillofacial surgeon, oncologist, pathologist, radiologist, anaesthetist, cancer nurse, restorative dentist, speech and language therapist and dietician (Dewan, Kelly and Bardsley, 2014).

Before the patient undergoes any oncology treatment, a consultant in restorative dentistry will assess whether the patient requires any dental interventions prior to commencing their treatment. Butterworth et al (2016) developed guidelines for the dental management of patients with head and neck cancer (Butterworth, McCaul and Barclay, 2016).

This pre-treatment assessment aims to:

- Avoid any unscheduled interruptions in treatment due to dental problems

- Plan in advance for any implants or obturators that are required

- Extract any teeth of dubious prognosis as early as possible

- Plan to restore any remaining teeth as required

- Provide preventative advice and treatment

- Assess for any potential post-treatment access difficulties such as trismus.

Therefore, the dentist must ensure the patient is dentally stable whilst undergoing treatment for their cancer. This means ensuring the patient can uphold a healthy oral cavity and rehabilitate following treatment (Hackett et al, 2019).

Preventative management of a patient includes ensuring their oral hygiene routine is optimised and maintained by effective toothbrushing and daily interdental cleaning.

Providing the patient with dietary advice and information with regards to sugar attacks and caries prevention is also key. Prescription of fluoride supplements such as high sodium fluoride toothpaste (5,000ppm) either brush-on or in custom trays (Epstein et al, 1996) and application of fluoride varnish (22,600ppm) following current Delivering Better Oral Health guidelines will also aid in prevention of decay.

Where possible and within reason, make attempts to save remaining key teeth to maximise restorative options (Beacher and Sweeney, 2018).

Adjust any sharp teeth or restorations. And polish to minimise the risk of traumatic injury to the tissues.

Due to time limitations and the risk of failure associated with endodontic treatment, its use is contraindicated for patients about to undergo oncological treatment.

Assess supporting structures. Extract any fully periodontally compromised teeth. Along with any teeth that are unrestorable or non-vital.

Current UK guidelines support the extraction of any teeth with dubious prognosis no less than 10 days prior to commencing oncology treatment to allow sufficient time for healing.

3. Peri- and post-treatment care

Undergoing oncological treatment to the head and neck region may involve radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgery. These entail a plethora of both short and long-term oral side effects.

Radiotherapy is often an adjuvant therapy to surgery.

Ionising radiation damages cellular DNA leading to cell death and destruction of the cancerous tissue.

However, to reach the cancerous tissue the beam must pass through multiple layers of oral tissue. This results in a range of side effects, including erythema, ulceration, trismus, dry mouth and osteoradionecrosis.

Following radiotherapy, the risk of osteonecrosis succeeding tooth extraction is high. Therefore we should make every effort to avoid extraction. Instead employing approaches such as endodontic treatment and coronectomy (Beacher and Sweeney, 2018).

Chemotherapy can lead to haematological side effects, such as immunosuppression. This has implications on the oral environment, such as increased incidence of infection.

If an acute dental infection is determined the dentist should liaise with the MDT allowing antibiotics as necessary.

The mainstay of oral cancer treatment continues to be surgical intervention. With oral rehabilitation following tumour resection carefully planned collaboratively between the maxillofacial surgeon, restorative dentist and a specialised lab technician.

However, the patient will still need ongoing support with their intensive dental maintenance. This will help preserve any remaining natural teeth and maxillofacial prosthesis.

Personalised oral hygiene instruction, fluoride application and supportive therapy from their dentist, hygienist or therapist is essential to preserve good oral health (Beacher and Sweeney, 2018).

Patients undergoing or who have undergone oncological treatment experience a wide variety of side effects. Each requires appropriate management to help minimise any pain and discomfort.

By identifying these side effects, dentists can provide appropriate advice and support. With the aim of making the patient as comfortable as possible.

Table 2 displays a list of short and long-term side effects and options for their management.

| Oral side effects and their management | |

| Side effect | Management |

| Short-term | |

| Mucositis and ulceration |

|

| Candidal infection |

|

| Long-term | |

| Altered anatomy |

|

| Dental caries

|

|

| Trismus |

|

| Mastication difficulties

|

|

| Osteoradionecrosis |

|

| Xerostomia |

|

Table 2: Adapted from Butterworth et al (2016), table displaying the short and long-term oral side effects of oral cancer treatment.

Summary

Oral cancer is a debilitating disease with a largely preventable aetiology.

With every diagnosis comes life-changing effects to the patient and their family.

The GDP assumes an important role in the journey of an oral cancer patient throughout. From the moment of screening and referral all the way through to remission.

The GDP can positively impact the patient’s quality of life by providing appropriate management and support along the way.

References

Awojobi O, Newton JT and Scott SE (2015) Why don’t dentists talk to patients about oral cancer? Br Dent J 218(9): 537-41

Beacher NG and Sweeney MP (2018) The dental management of a mouth cancer patient. Br Dent J 225(9): 855-64

Butterworth C, McCaul L and Barclay C (2016) Restorative dentistry and oral rehabilitation: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 130(S2): S41-4

Dewan K, Kelly RD and Bardsley P (2014) A national survey of consultants, specialists and specialist registrars in restorative dentistry for the assessment and treatment planning of oral cancer patients. Br Dent J 216(12): E27

Epstein JB, Silverman S Jr, Paggiarino DA, Crockett S, Schubert MM, Senzer NN, Lockhart PB, Gallagher MJ, Peterson DE and Leveque FG (2001) Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis: results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cancer 92: 875-85

Epstein JB, van der Meij EH, Lunn R and Stevenson-Moore P (1996) Effects of compliance with fluoride gel application on caries and caries risk in patients after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 82(3): 268-75

LeHew CW, Epstein JB, Kaste LM and Choi Y (2010) Assessing oral cancer early detection: clarifying dentists’ practices. J Public Health Dent 70(2): 93-100

Hackett S, Jones O, Chatzistavrianou D and Newsum D (2019) Head and neck cancer part 2: the patient journey. Dent Update 46(9): 817-24

Harding J (2017) Dental care of cancer patients before, during and after treatment. Br Dent J Team 4: 17008

Macpherson LMD, McCann MF, Gibson J, Binnie VI and Stephen KW (2003) The role of primary healthcare professionals in oral cancer prevention and detection. Br Dent J 195: 277-81

McGurk M, Chan C, Jones J, Oregan E and Sherriff M (2005) Delay in diagnosis and its effect on outcome in head and neck cancer. Br J Oral and Maxillofac Surg 43(4): 281-4

Murphy BA, Gilbert J, Cmelak AJ and Ridner SH (2007) Symptom control issues and supportive care of patients with head and neck cancers. Clin Adv Haematol & Oncol 5(10): 807-22

Papas A, Russell D, Singh M, Kent R, Triol C and Winston A (2008) Caries clinical trial of a remineralising toothpaste in radiation patients. Gerodontology 25: 76-88

Scully C and Kirby J (2014) A Statement on Mouth Cancer Diagnosis and Prevention. Br Dent J 216(1): 37-8

Van der Waal I, de Bree R, Brakenhoff R and Coebergh J (2011) Early diagnosis in primary oral cancer: is it possible? Medicina Oral Patologia Oral Cirugia Bucal 16(3): e300-5