Corporate dentistry: three decades of transformation

Corporate dentistry: three decades of transformation

Over the past three decades, the business of dentistry has undergone a quiet but significant transformation. Once dominated by solo and small-group practices, the profession has seen the steady rise of corporate dentistry and dental service organizations (DSOs), reshaping the ownership, management and delivery of care.

This evolution has brought both opportunities and challenges. Corporate groups have introduced business efficiencies, new career pathways, and practice models that simply didn’t exist a generation ago. At the same time, concerns around clinical autonomy, patient experience, and the role of profit in healthcare continue to spark debate across the profession.

In this article, leading experts chart the journey of corporate dentistry – from its early consolidation trends to its current scale and influence.

Kicking things off, Ian Gordon takes us back to the formative years of corporate dentistry. He charts how legal restrictions, NHS contract reforms and private equity investment combined to shape the first wave of corporate growth, setting the stage for today’s market dynamics.

From there, Neel Kothari reflects on the impact corporates have had on the day-to-day life of clinicians. Drawing on his own experience, he examines both the opportunities – investment, governance and training – and the drawbacks, including a loss of personal connection and the variability in management quality.

Len D’Cruz explores how corporate structures have affected clinical autonomy and the wider workforce. He considers the changing expectations of younger dentists, the pressures of working under the NHS contract, and the balance between stress-free environments and professional independence. He also turns to indemnity, showing how corporates manage risk and complaints – and what this means for associates navigating today’s litigious climate.

Chris Barrow then steps back to examine the market forces that have shaped corporate dentistry. From rarefied ownership ‘badges’ in the 1990s to the private equity boom of the 2000s and the more complex, segmented market of today, he traces the business models that have risen, merged and evolved.

Looking ahead, Anushika Brogan considers whether corporates represent the future of dentistry. She highlights the efficiencies and opportunities that come with scale, from digital investment to career progression, while acknowledging the risks of depersonalisation and loss of autonomy.

Finally, Ian Gordon returns to cast his eye forward to the next five years. He sets out the challenges and opportunities on the horizon – from contract reform and CMA oversight to digital adoption and workforce shortages.

Together, their perspectives shed light on how corporates are changing the landscape for clinicians, patients and the workforce, and explore a pressing question for the future: is corporate dentistry here to stay?

Early days of corporate dentistry – Ian Gordon

Early days of corporate dentistry – Ian Gordon

The early days of corporate dentistry

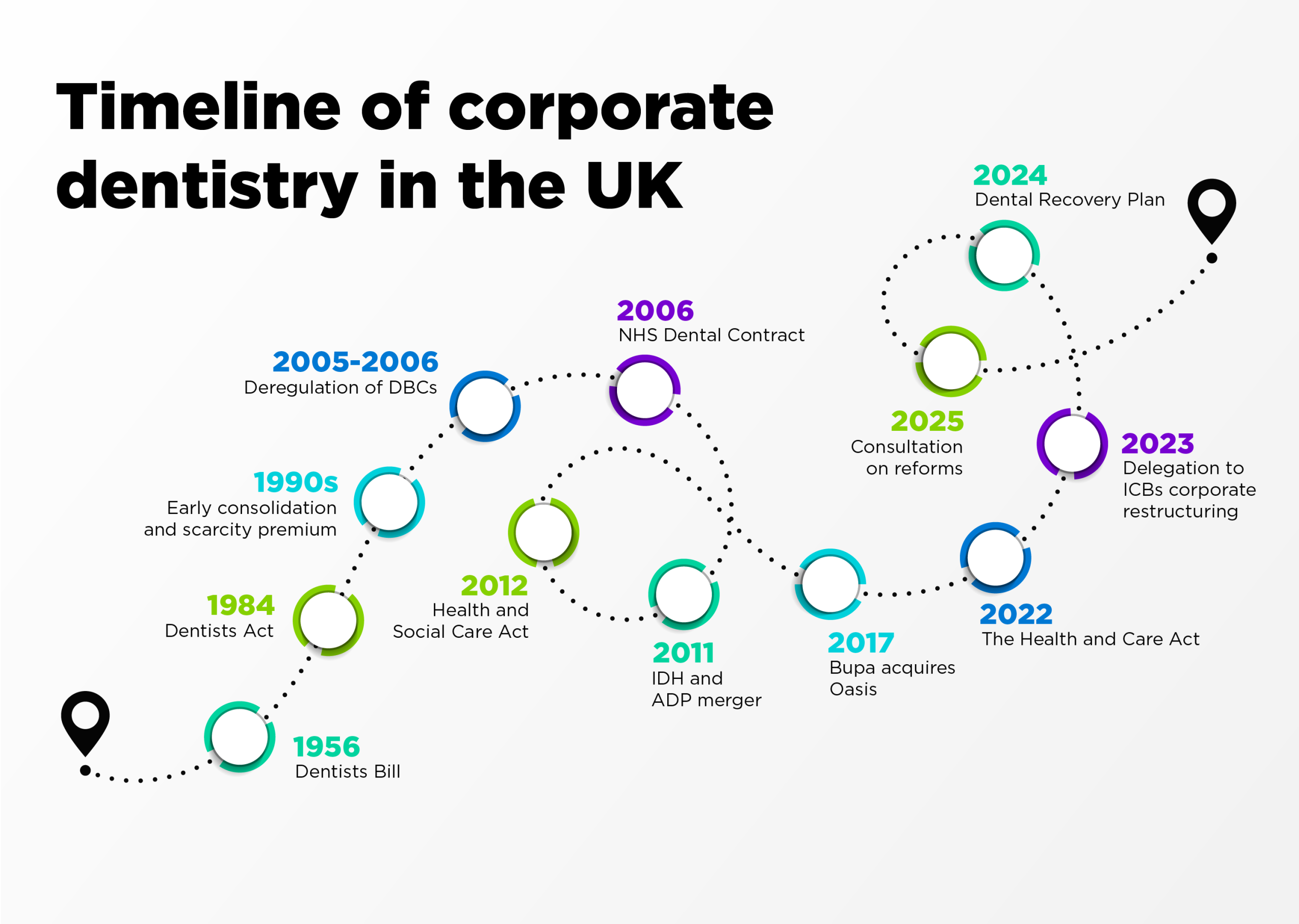

For much of the 20th century, only a small, fixed list of companies could lawfully carry on ‘the business of dentistry’. In 1956 the Dentists Bill received royal assent with 74 DBCs (dental bodies corporate) listed and ‘grandfathered’. No new ones could be created. By 2002 that list had dwindled to 27.

The Dentists Act 1984 consolidated the regime and kept the restriction to the existing DBCs. A 2005 amendment order (taking full effect in July 2006 via General Dental Council (GDC) rules) removed the old cap and allowed unlimited DBCs, provided a majority of directors were GDC-registered dentists or dental care professionals (DCPs).

Because only a fixed list of DBCs could trade until 2006, the corporate ‘shells’ commanded significant scarcity premiums, although precise market prices weren’t routinely published. Anecdotally, DBCs traded for very high sums. They were the key gateway to practice ownership at scale at a time (in the 1990s) when practice goodwill was between 25% and 60% of turnover.

I acquired my first practice in 1989, building a small group of four practices (The Dental Centre) over the next 17 years before selling in 2008 to IDH. I remember being offered around 30% of turnover in 2004 by another growing group, which was by then establishing itself on Teesside. There is no doubt that the 2006 dental contract and the de-restriction of DBCs had a major impact.

The 2006 NHS dental contract introduced banded treatments and units of dental activity (UDAs). For many practices, fixed annual UDA volumes created strong incentives to systematise operations – an area where corporates could excel through scale, centralised support and data. The late 1990s and 2000s therefore saw the emergence of scale players (IDH/Mydentist, ADP, Oasis), often backed by private equity.

By 2011, IDH and ADP had merged and, by 2017, Bupa (a not-for-profit) had acquired Oasis, cementing corporates as mainstream providers.

The rise of corporates and DSOs – Ian Gordon

The rise of corporates and DSOs – Ian Gordon

Emerging consolidation trends

Buy-and-build, then pause, then pivot

From roughly 2015-2022, roll-up strategies accelerated, backed by private equity and cheap debt.

Since 2023, higher interest rates and recruitment challenges have slowed the pace and shifted emphasis to portfolio optimisation, operational excellence and selective mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in private-leaning markets and specialist niches such as implants, orthodontics and sedation.

Market structure

Independents still account for the majority of UK practices, but the share run by larger groups continues to rise. Corporates with more than 30 sites now represent a meaningful minority of locations, with mid-sized groups also growing – pointing to a long runway for further consolidation.

During this time I have been actively involved in the development of Riverdale Healthcare, backed by Apposite Capital. After the sale of The Dental Centre in 2008, I founded Vitality Dental Practice and Alpha Dental Group in North Yorkshire. Along with my wife and business partners, we built a 10-practice group which was acquired by Riverdale in 2018 as their platform investment.

My business partner Ben Wild and I are directors of Riverdale and have been part of the journey which has seen the group grow to 60 practices across the North-East, North Yorkshire, North West, East and West Midlands, Cambridge and Essex – led by an experienced executive team of which we are part.

This personal involvement has allowed me to witness the growth of the corporate sector – the growing pains and the rewards.

The rise of corporates and DSOs

In UK terminology, ‘corporates’ usually own practices (often via DBC structures). The term ‘DSO’ is borrowed from the US and emphasises non-clinical support (HR, finance, marketing, procurement, compliance, IT) provided to clinician-led practices.

In reality, UK models sit on a spectrum:

- Wholly owned corporates (eg Mydentist, Bupa Dental Care, Colosseum) with centrally run support functions

- Partnership-style platforms (eg Dentex historically) where clinicians retain equity while the centre provides DSO-style support

- Hybrid groups mixing NHS, private and specialist income, increasingly adding affordable private products and subscriptions to hedge UDA risk.

Why has the model has grown?

- Scale efficiencies in recruitment, procurement, compliance and digital patient acquisition

- Access to capital for greenfield sites, refurbishments, digital equipment (CBCT/scanners) and bolt-ons

- Career paths and clinical governance frameworks that appeal to graduates and returners.

Regarding risks and critiques, NHS viability under UDA constraints has driven portfolio churn, closures and privatisation of capacity in some areas. Local competition concerns attract CMA scrutiny on mergers. Workforce remains a binding constraint; scale helps but does not fully solve regional supply.

Corporates: an opportunity or obstacle? – Neel Kothari

Corporates: an opportunity or obstacle? – Neel Kothari

Corporates are ‘here to stay’ – but do they benefit clinicians?

Dental corporates have had an explosion in prevalence since 2005 where an amendment to the Dentists Act 1984 led to a removal of the restrictions a corporate body may own.

Prior to this, a dental corporate body could own up to 10 practices where the majority of directors had to be dentists.

This kept the corporate entities relatively small, localised and limited in scale.

Their rise has been met with mixed reception within the profession, but now that the genie is out of the bottle, they are well and truly here to stay.

Their potential benefits are huge as they often have the capital to invest heavily in modern facilities and technologies, clinical governance policies that are standardised, as well as improved access for patients by setting up in areas historically difficult to attract dentists, and provide non-monetary benefits such as training/mentoring pathways.

Despite these appreciable benefits, anecdotal evidence would suggest that they have mixed reviews within the profession.

It isn’t uncommon to see social media posts highlighting some of the challenges of working for a corporate, with others squarely setting out how they would never work for another corporate ever again.

Having worked for a corporate myself in the past as an associate, I can say my experience was indeed mixed – not entirely bad, but different to what I had expected.

A little like eating at a Bella Italia in a business park – you know what you are going to get, but it’s not exactly a small family-run restaurant.

Now, this isn’t a criticism, because both corporates and independently owned practices offer different sets of advantages and disadvantages, but what seems to be missing from many corporates is the ability to have a personal touch over the staff that work there, which isn’t surprising as the workers are unlikely to ever meet the owners.

This makes the skillsets of the management team a considerable factor in how well a corporate is run.

Corporate dentistry and clinical autonomy – Len D’Cruz

Corporate dentistry and clinical autonomy – Len D’Cruz

What impact has corporate dentistry had on clinical autonomy?

Corporate ownership of dental practices, driven by profit and returns on investment alongside the delivery of healthcare, might once have made uncomfortable bedfellows. Things have moved on since the deregulation of corporate dentistry by the GDC in 2006 and, while the size of corporates ranges from four or five practices (mini-corporates) to over 500 in some cases, associates working within them hold varying views, just as they do with principal dentist-owned practices.

The relationship between clinicians and middle management raises issues (Westgarth, 2025), such as control and pay.

One thing that is changing is that dentists in their 20s and 30s have recognised much earlier than previous generations that dentistry is stressful – physically, mentally and sometimes emotionally draining as well. They do not necessarily want damaging levels of cortisol coursing through their bodies for the next three to four decades, and they have voted with their feet to do three things: remain as associates rather than buying practices, move away from the NHS, and work part-time while occupying themselves with pursuits outside clinical dentistry.

An increasingly larger proportion of the workforce being female makes this transition both obvious and logical.

While the NHS contract in England has remained largely unchanged since 2006 – apart from some marginal adjustments in the last couple of years – the dogged loyalty and allegiance older practitioners had to the NHS is no longer present in the next generation. They feel the obvious unfairness of the payment mechanism is not something they wish to tolerate.

Corporate dentistry, in some cases, provides the environment for associates to flourish and grow, supported by CPD programmes, specialist colleagues, and support staff, allowing them to deliver the dentistry they want to provide for their patients.

Clinicians value their autonomy, but also appreciate a stress-free environment where they do not have to worry about whether the nurse is experienced and competent, whether the equipment works, or whether all the materials are in stock and of reasonable quality.

Indemnity issues arising out of corporate dentistry

Complaints in a service industry where money changes hands are an inevitable by-product of dental care delivery, and good corporates manage them well, recognising that there is as much peril for the clinician as for the practice and the corporate brand.

Indemnity organisations like to work with their members to support them through sometimes stressful complaints, litigation or a GDC investigation. It helps if the corporate provides the same support for their clinicians so that complaints do not escalate.

There are often layers of bureaucracy in corporates, absent in family-run practices, that conspire to slow response times. This only adds to patients’ frustration.

Some corporates provide indemnity to associates through a single scheme that covers both the entity (the corporate) and the individual associate. This carries the risk of conflict, as the corporate’s interests may not align with the position an associate takes.

References

Westgarth D (2025) ‘In their own words: Associates working in corporates’. BDJ In Practice 38: 266-7

How have corporates shaped the market? – Chris Barrow

How have corporates shaped the market? – Chris Barrow

Structure, compliance and buying power

I first realised that corporate dentistry was here to stay back in the 1990s.

At the time, you could only operate a corporate if you owned one of a handful of grandfathered businesses permitted to trade as limited companies.

These ownership ‘badges’ were so rare they changed hands for £250,000 – a quarter of a million pounds for the privilege of entering the market. That was the moment it became clear this wasn’t a passing phase, but the beginning of something bigger.

The 1990s saw the first wave of consolidation, led by pioneers like Integrated Dental Holdings. Initially, the concept was unfamiliar – even slightly risky. The few players operating at scale were still outliers in a profession dominated by small, owner-managed practices. But the seed had been planted.

The early 2000s brought a seismic shift: the introduction of NHS contracts. Private equity investors quickly recognised these as a guaranteed income stream from government. The capital flowed in, and large groups scaled aggressively.

By the mid-2000s, clinical recruitment had gone global – continental Europe and India became primary sources of dentists to fill rapidly multiplying chairs.

In the years leading up to COVID-19, a new pattern emerged: the rise of smaller corporate groups and the steady pipeline of independent practices selling into them. Valuation multiples soared in what can only be described as feeding frenzies, with the ‘earn-out’ model becoming the norm for larger transactions.

How did the market change post-COVID?

Post-COVID, the picture shifted again. Smaller groups multiplied, while the larger players focused on consolidation – sometimes into ‘super-centres’ – or on overseas acquisitions at more modest valuations.

One of the most persistent claims from corporates is that they grant their clinicians full clinical freedom. In reality, the truth is more complex. While many do provide genuine latitude in treatment decisions, the economic pressures of a struggling economy inevitably tighten the screws on operating costs.

The result? A paradox: autonomy on paper, alongside increasing constraints on resources and delivery models.

From a career perspective, I would argue that independent practices often offer greater personal growth. Corporates have the structure, compliance systems, and buying power – but also more rigid protocols.

The myths? Job security in a large group is not guaranteed. Innovation in digital workflow and AI-driven business systems is, in my view, slower in corporates than in agile independents. And while over 75% of UK NHS patients are treated by corporates, that doesn’t automatically translate to universal access.

Looking to the future of the corporate market

Chris sees the market segmenting into five clear models:

- Institutionally owned corporates backed by insurers and healthcare giants

- Private-equity-backed mid-sized groups

- DSOs offering support services without equity ownership

- Shared-equity businesses enabling younger dentists to buy in over time

- Independents, increasingly drawn to DSO-style support while retaining ownership.

The great differentiator will be technology. Digital workflow and AI-driven systems will separate leaders from laggards – and independents currently have a decisive advantage in agility and adoption.

Corporate dentistry has indeed come of age, but scale alone is not the future. The winners will be those – corporate or independent – who adapt fast, invest wisely, and keep their clinical and commercial vision aligned.

Is corporate dentistry the future? – Anushika Brogan

Is corporate dentistry the future? – Anushika Brogan

Advantages versus challenges

The dental landscape has changed dramatically over the past two decades, and corporate dentistry has been central to that change. At its simplest, it means operating multiple practices under one group structure – sharing resources, centralising support, and creating opportunities on a scale that independent practices often struggle to achieve.

The advantages are clear. By taking non-clinical functions such as HR, compliance and finance out of the surgery, clinicians are free to focus on what matters most: patient care.

Scale also brings investment. Access to the latest technology, from 3D scanners to advanced imaging, is accelerated when purchasing power is pooled, and corporates have been instrumental in driving the digital transformation of dentistry.

But scale brings its own challenges. Recruitment difficulties, rising patient demand, and the need to safeguard clinical independence can all act as a brake on growth. For corporate dentistry to succeed, it must strike a balance between business efficiency and professional autonomy.

When clinicians are trusted to lead, supported with mentoring, training, and the right resources, the model works. When they are not, the risk is a system that prioritises processes over patients.

Shifting perceptions

One of the defining features of corporates is their ability to create new career pathways. Beyond the traditional associate model, there are routes into leadership, mentoring, and specialist roles, supported by structured progression frameworks and flexible working options.

For overseas dentists, corporates often provide a defined entry point, bringing fresh skills and perspectives into UK practices. This is changing the way people think about a career in dentistry – broader, more sustainable, and with opportunities for growth that once didn’t exist.

There is also real potential to shift the make-up of dental leadership. Larger organisations have the ability to embed inclusive recruitment and development strategies, ensuring more diverse representation at senior levels.

That matters, because dentistry should reflect the communities it serves – not only in patient care, but in the voices shaping its future.

Perceptions of corporate dentistry are evolving. Once seen as impersonal and ‘one-size-fits-all’, the model is increasingly understood as flexible, patient-centred, and supportive of clinicians when done well. Independent practices will always have an important place, but corporates are now a permanent feature of the profession, shaping its direction and raising expectations.

The question isn’t whether corporate dentistry is the future – it is already here. The challenge now is to ensure it grows in a way that protects autonomy, values diversity, and keeps patient care at the heart of everything we do.

What to watch over the next five years – Ian Gordon

What to watch over the next five years – Ian Gordon

What do the next five years hold for corporate dentistry?

Contract reform

Will UDAs be reshaped or supplemented by access/prevention metrics? Expect ICB‑level pilots and variation, however, ICBs are constrained by central government demands for 50% cuts in their workforce.

Some are considering the previously impossible: given the economic situation and the fact that NHS dentistry is not funded to deliver care to 100% of the population, the government might define the scope of care to match its election pledges regarding access to urgent care and prevention.

Some honesty in this area would help, and the profession will find a solution to continue to care for those the NHS deems ‘not needing regular NHS care’, certainly not on a six‑month recall basis.

Such a change would likely accelerate the growth of private dentistry – especially affordable private plans, membership and transparent pricing.

Buy‑and‑build 2.0

M&A is likely to be selective. Greenfield site returns improve where recruitment and local demand are strong.

CMA guardrails

Local market tests will keep roll‑ups disciplined and may spur creative deal structures.

Workforce and skill‑mix

Expanded roles for therapists/hygienists; investment in mentoring, supervision and productivity tools.

Digital operations

CRM/recall science, AI‑assisted diagnostics/documentation and practice analytics as core competitive differentiators. Those that embrace AI will, I predict, see major benefits in terms of their ability to attract both clinicians and investment.

ASUB

Fifteen years ago, a new trade association – the Association of Dental Groups (ADG) – was established, led by the talented and, sadly, late David Worskett. This brought together IDH, Oasis, Rodericks and Portman, and grew steadily to include all the major corporate groups.

Dental deserts

Alpha joined in the early days; I have served as a director and am currently special adviser to chair, Neil Carmichael. The ADG works closely with the BDA and interfaces with government, regulators and the wider profession.

In recent years its work established the phrase ‘dental deserts’, focusing on the challenges of recruitment. Workforce remains the biggest barrier to the expansion of NHS and private corporate or independent practices.

It is simply disingenuous to suggest that an improved NHS contract will solve the access crisis – it will not. In some areas of the country it is impossible to recruit to a private‑only role; how would an improved NHS contract change that situation?

ORE challenges

There are over 2,000 dentists already living in the UK with overseas qualifications. The GDC has it within its gift to solve the crisis of ORE examination numbers which block registration. Until numbers of dentists on the register increase, the access problem will not improve.

Indeed, if the proposed April 2026 reforms are not funded adequately (and there is a significant risk they will not be), the situation could well get worse.

Stay updated with relevant information about this webinar