In this article, Chris Harris makes the case that understanding cranial osteopathy isn’t just relevant to dentistry – it is essential.

Is an understanding of cranial osteopathy relevant for dentistry? Yes, it is. In fact, I would argue that it is not only relevant but essential. The following is a condensed whistlestop tour of some important points. It will likely stimulate more questions than provide answers, but these questions will be welcome.

Cranial osteopathy: a brief explanation

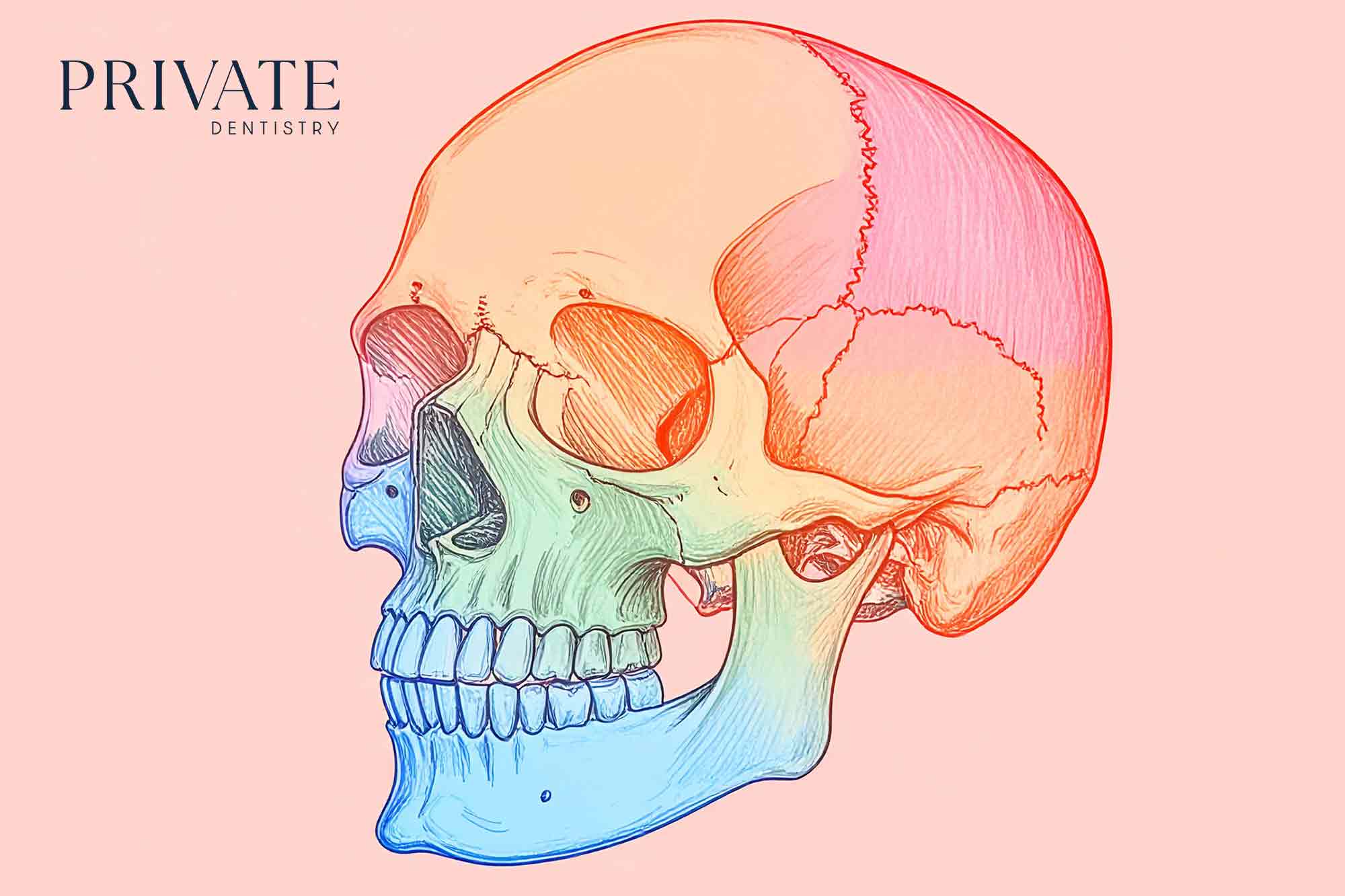

The fontanelles in an infant skull close over as the bones grow together, the largest at the vertex at about 18 months. The skull then fuses into a solid one-piece structure: this is the understanding of most medics. The bones are initially separate at birth to allow a needed shape adaptation for a vaginal birth. This is not correct: they do not fully fuse. They approximate, interdigitate and form joints – joints designed for movement.

The anatomy of the sutures suggesting this was spotted by Dr Sutherland in 1899. He was student of the original osteopath Dr Still. Anyone with a little patience can feel the movement with their hands.

The movement is often described as fluid pump for the cerebrospinal fluid. With patients I talk about a slow-motion heartbeat of the nervous system: roughly eight cycles a minute. The whole body minutely changes shape, a bit like a big domed jellyfish as it moves along. We call it flexion and extension.

Sign in to continue reading

Free access to our premium content:

- Clinical content

- In-depth analysis

- Features, reports, videos and more

By joining, you’re helping to support independent, quality journalism that keeps dental professionals informed and empowered – and allowing us to keep delivering the insights you value most.